Protecting elections in the face of natural hazards

Natural hazards not only present a huge humanitarian threat but also unparalleled challenges to electoral stakeholders seeking to protect electoral integrity during emergencies.

Events like floods, hurricanes, heatwaves, and wildfires can trigger the postponement of elections, affect campaigns, and impact electoral operations and the choices that voters make.

Between January 2019 and May 2024, more than 20 countries were affected by natural hazards during subnational or national elections (see table 1). In the Asia-Pacific in 2024 alone, India, Indonesia, Iran, Maldives and Tuvalu have all been struck by acute weather events during national elections.

Table 1. Countries by region affected by natural hazards during elections from January 2019 to May 2024

| Africa | Americas | Asia-Pacific | Europe |

| Malawi | Belize | Australia | Gerrmany |

| Mozambique | Canada | India | Italy |

| Somalia | Ecuador | Indonesia | Spain |

| Sout Africa | USA | Iran | Türkiye |

| Maldives | |||

| Pakistan | |||

| Papua New Guinea | |||

| Tuvalu |

What type of hazards impact elections?

To date, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) has identified 41 cases in which natural hazards have had impacts on national and subnational elections in 27 countries from all regions of the globe.

In many of these cases, there are links to climate change.

The natural hazards most frequently affecting elections are riverine flooding, hurricanes, and wildfires (see table 2).

Table 2. Types and frequencies of natural hazards affecting elections

Authors constructed using International IDEA country briefs, media and election observation reports. Note: This table is based on 27 countries that held 41 elections from August 2007 to May 2024. Note: some elections were affected by more than one type of natural hazard.

When do natural hazards impact voting?

As witnessed in the 2019 elections in Mozambique and the 2023 elections in Türkiye, natural hazards can have a large impact on voter registration.

In Mozambique, cyclone Ida hit the country during the voter registration phase. The cyclone destroyed roads and electricity infrastructure, resulting in a 15-day postponement of voter registration.

Beyond voter registration, disruptions to voting day itself can present the greatest threat to electoral integrity. Out of the 41 cases identified, 77% of voting operations were interrupted by natural hazards in national elections and 73% in subnational elections. In cases where natural hazards impact voting operations, election officials face damaged infrastructure, voter and ballot transportation concerns, closed polling stations, loss of voting equipment, lack of identification documentation, and insufficient numbers of frontline and temporary staff.

Overall, the 41 cases demonstrate that natural hazards can impact every phase of the electoral cycle. This also includes the campaign period, seen in a summer heatwave during a snap election in Spain and frigid winter temperatures during the Iowa caucus, which forced candidates to change rally venues and cancel events.

Can disasters cause the postponement of an election?

In some cases, the impacts of a natural hazard are greater than an electoral management body can mitigate. This is especially true for rapid-onset disasters, such as hurricanes and flash flooding, that are more prevalent in their impact on elections.

When rapid-onset hazards arise, different permissions in a country's electoral framework allow for election postponement.

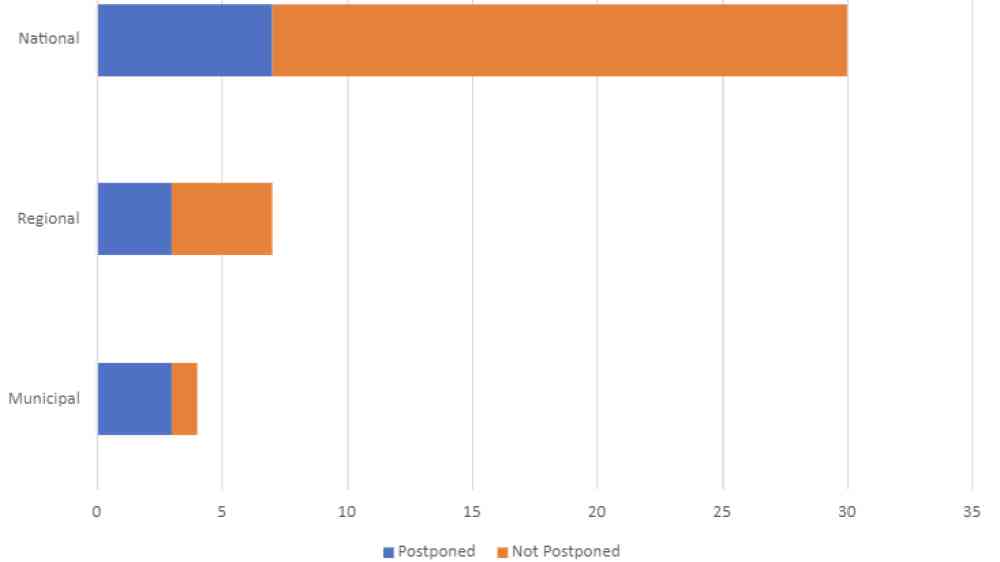

In 13 out of the 41 cases that experienced a natural hazard during the electoral cycle, elections were postponed. In some cases, these involved postponements for the whole country, and in others just specific regions, depending on the scale of the hazard (see table 3).

Table 3. Postponed elections due to natural hazards

Source: Authors constructed using International IDEA country briefs, media and election observation reports. Note: This table is based on 27 countries that held 41 elections from August 2007 to May 2024.

How can elections be protected?

Electoral authorities will never be able to plan for all eventualities, but there are several things that can be done to make elections resilient.

Many natural hazards are seasonal, and where the constitution allows, it is advisable to hold elections at times of the year when disasters are least likely. It is also important for electoral authorities to coordinate with other agencies - meteorological, disaster relief and humanitarian branches of the state as well as relevant non-state actors - to use early warning techniques that may identify potential hazards in the run-up to elections, and to ensure that there are plans in place for joint working during disasters if the need arises.

For example, in the eastern part of South Africa, the provincial Election Management Body (EMB) set up tents to be used as polling stations when floods that hit the region immediately before the 2019 general elections.

Preparatory activities may include regular staff training, contingency funding mechanisms and standing joint working arrangements across local or national agencies.

In Australia, the Victorian Election Commission regularly meets with Emergency Management Victoria before state elections.

Voter registration and voting are two points in the election cycle that are especially vulnerable to disruption by natural hazards. Resilient election procedures include voter registration processes that are not so localized and paper-based that electoral authorities could lose track of displaced voters with no means of including them in the electoral process.

Resilient election processes also have special voting arrangements built into them, including mobile ballot box voting and special polling stations for displaced electors and - where possible - postal voting. If electoral authorities have plans and procedures in place that are flexible, they will find it much easier to cope with the sorts of hazards that are most disruptive to elections.

Elections as part of critical infrastructure

As extreme weather exacerbated by climate change will continue to wreak havoc around the world, states should recognize democratic institutions and processes, not least elections, as critical infrastructures whose functioning is deeply affected by disasters. This could help guarantee the delivery of the public goods and services they are designed to ensure.

Moreover, there is a need for more cross-cutting and multidisciplinary engagement between the election, climate change and disaster risk reduction communities. This would strengthen peer-to-peer exchange and learning across silos and ultimately help to build a better understanding of what can be done to protect elections and enfranchise voters in the face of natural hazards.

For more information visit International IDEA

See publications produced by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors, one of whom is a staff member of International IDEA. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

Erik Asplund is a Senior Programme Officer in the Electoral Processes Programme, International IDEA. His research covers elections during emergencies and crises, risk management in elections, and training and professional development in electoral administration. Recent publications include Elections during Emergencies and Crisis: Lessons from Electoral Integrity from Covid-19 Pandemic.

Maddie Harty is an independent consultant. Her work includes contributions to the Impact of Natural Hazards on Elections, the Global Election Monitor, and trainings on electoral administration. Her MA in International Security from the Josef Korbel School of International Studies focuses on democracy and peacebuilding.

Sarah Birch is a professor of political science in the Department of Political Economy at King's College London. She conducts research on electoral integrity and the political effects of climate change.

Ferran Martinez i Coma is Senior Lecturer in the School of Government and International Relations at Griffith University (Brisbane, Australia). He is an applied political scientist with consulting, public policy, research, and teaching experience. His research specializes on participation, electoral integrity, and electoral systems.