Crowdsourced reports via app can quickly identify an earthquake’s impact as high or low

After an earthquake, it is crucial in the early phase of disaster management to obtain a rapid assessment of the severity of the impact on the affected population in order to be able to initiate adequate emergency measures. A first quick and good assessment of whether an earthquake causes severe or minor damage can often be given after only 10 minutes by information from affected people about the “felt intensity” of the earthquake. This is shown in a recent study by researchers led by Henning Lilienkamp and Fabrice Cotton from the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, which has now been published in the journal “The Seismic Record”. In their new approach, they use crowdsourced data and evaluate the information that people have transmitted after a quake via a website or app of the Last Quake service of the European Mediterranean Seismological Center. Since no seismic measurement data is required, this low-cost approach may assist disaster management in the future, especially in regions where there are few measuring devices.

Background: Assessing the impact of an earthquake

Being able to assess the impact of an earthquake as quickly as possible is essential for decision-makers and disaster managers, as it directly influences which measures are taken to protect lives and limit further damage.

In some cases, such as the catastrophic series of earthquakes in Turkey and Syria in February 2023, it is immediately clear that large-scale emergency response is urgently needed. But this is not always true.

“For example, in the magnitude 5.9 earthquake that struck remote areas of Afghanistan and Iran on 12 June 2022, causing more than 1,000 deaths, it was not clear for hours whether significant impacts were to be expected or not, according to the European Mediterranean Seismological Center (EMSC),” explains Henning Lilienkamp, PhD student in the “Earthquake Hazards and Dynamic Risks” section at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences and lead author of the current study.

There are rapid assessment systems such as PAGER, which was developed by the U.S. Geological Survey. However, it currently takes an average of about 30 minutes to then already give quite extensive estimates of the effects of an earthquake. And it is based on the ShakeMap method, so it needs ground acceleration data and other seismic observations as well as reports from the population.

New approach based exclusively on felt reports

“Many types of data can be included in the assessment of an earthquake and its immediate consequences, and a differentiated analysis is crucial for successful long-term disaster management,” emphasizes Lilienkamp. He and his colleagues have now been able to show that an initial rough but often quicker assessment is already possible based solely on information from the affected population. In addition to Henning Lilienkamp and Fabrice Cotton, head of the “Earthquake Hazards and Dynamic Risks” section at the GFZ and professor at the University of Potsdam, other researchers from the University of Potsdam, the EMSC, and the University of Bergamo were also involved in the study, which was published in the journal “The Seismic Record”.

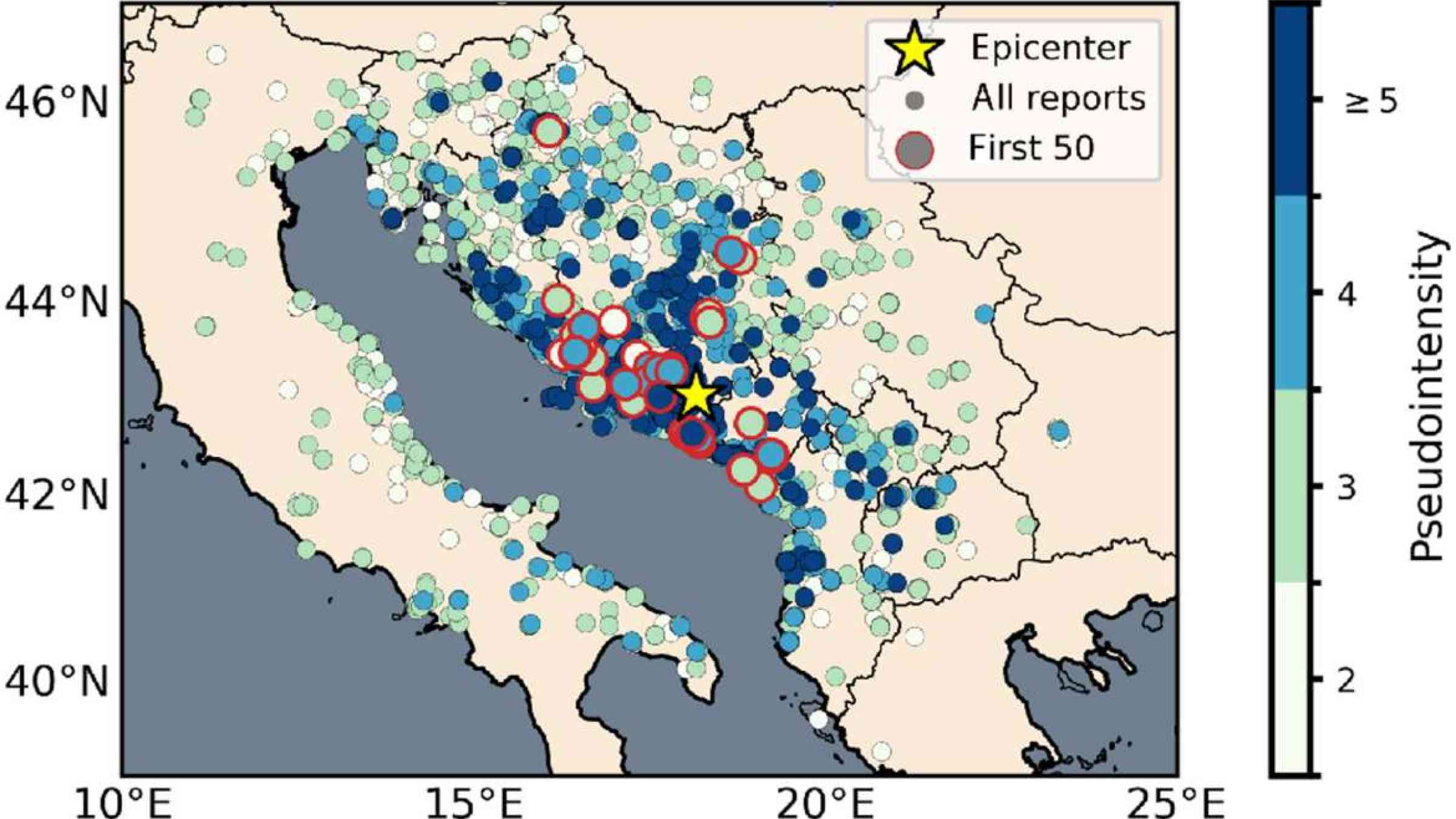

In their new approach, they use crowdsourced data on the “felt intensity” of an earthquake from affected people. The latter transmit their personal assessment after the earthquake based on a graph and a comment via the website or app of the EMSC's LastQuake service. It was developed to warn people as quickly as possible immediately after a quake. Already in the first 10 minutes after an event, a large data set might be available for evaluation, though this number of course depends on the strength of the earthquake and the level of the populations’ participation.

For example, for the 6 February quake sequence in Turkey, the LastQuake service collected about 6500 reports for the first 7.8 magnitude earthquake and about 4800 reports for the second 7.5 magnitude earthquake, according to Lilienkamp. For the first quake, it took about 4.5 minutes to collect 50 reports – the minimum number needed to run the model developed here – and after 10 minutes, already 1232 reports were available.

“We were convinced that this database is too valuable to be disregarded in the long run, because it is collected efficiently and on a global scale, including in regions that lack expensive seismic instrumentation,” says Lilienkamp.

Development of a model for rapid assessment of quake effects

The researchers had access to more than 1.5 million globally collected reports on the perceived intensity of more than 10,000 earthquakes of any magnitude from 2014 to 2021. Based on this “crowdsourced data”, they developed a probabilistic model that can be used to estimate whether an earthquake has a high or low impact.

For this purpose, in a step one the perceived intensity data of past earthquakes were converted into representative parameters, such as a “pseudo-intensity value” that quantifies the extent of the shaking. Another value describes the spatial extent of the area in which the ground shaking was felt.

In a second step, the associated earthquakes were classified using more detailed information from global earthquake impact databases. The study defines earthquakes with strong impacts as those associated with at least one of the following impacts: one destroyed building, at least 50 damaged buildings, at least two fatalities or documented financial losses.

In the end, this results in a statement about how probable it is that an earthquake with the transmitted “felt” information has strong impacts.

Step one can then also be used to classify new earthquakes.

Validation and limitation of the new approach

The researchers then tested their model on eleven earthquakes from 2022. “A key strength of our approach is that it is very quickly able to correctly and unambiguously assess a large number of events with a low impact,” Henning Lilienkamp sums up.

Being able to identify an earthquake as low impact could provide some comfort to the public, as these kinds of earthquakes – although not too strong – can still be felt and may cause anxiety as a result, the researchers note in their paper.

“We see with high-impact events that it remains a challenge to clearly distinguish them from lower-impact ones as well,” Lilienkamp says. This may also be due to the fact that the underlying data set on which the model has “learned” naturally contains much fewer severe earthquakes. With data collected over time, this could improve further, the researchers estimate.

A natural limitation of the approach – especially during strong earthquakes – is the lack of very early reports from the area where the shaking was most intense. “This effect is well known and represents the fact that people under such extreme circumstances of course prioritize finding shelter and rescuing people in danger, over submitting felt reports on their smartphones,” explains Lilienkamp. Furthermore, the global analysis shows that the LastQuake service is currently still predominantly used in Europe (75 per cent of the data comes from there).

“We see our method as a cost-effective addition to the pool of earthquake impact assessment tools that is completely independent of seismic data and can be used in many populated areas around the world. Although it remains an open task to further develop our method into a tool for practical use, we show the potential to support disaster management in regions that currently lack expensive seismic instruments,” says Fabrice Cotton from GFZ.

Outlook: Application potential

Lilienkamp and colleagues suggest that their method could be used to develop a “traffic light” system based on impact scores, where green-level scores would require no further action by decision-makers, yellow would prompt further investigation and red could raise an alert.

“As seismologists, we need to get a better understanding of how exactly decision-makers and emergency services like fire departments actually act in case of an emergency, which kind of information is useful, and at which probabilities of high impact they would prefer to raise an alarm,” said Lilienkamp. “Careful communication of our model’s abilities and the individual needs of potential end-users will be key for a practical implementation of traffic-light systems.”