Beating the heat in South African cities: Lessons from a citizen science assessment

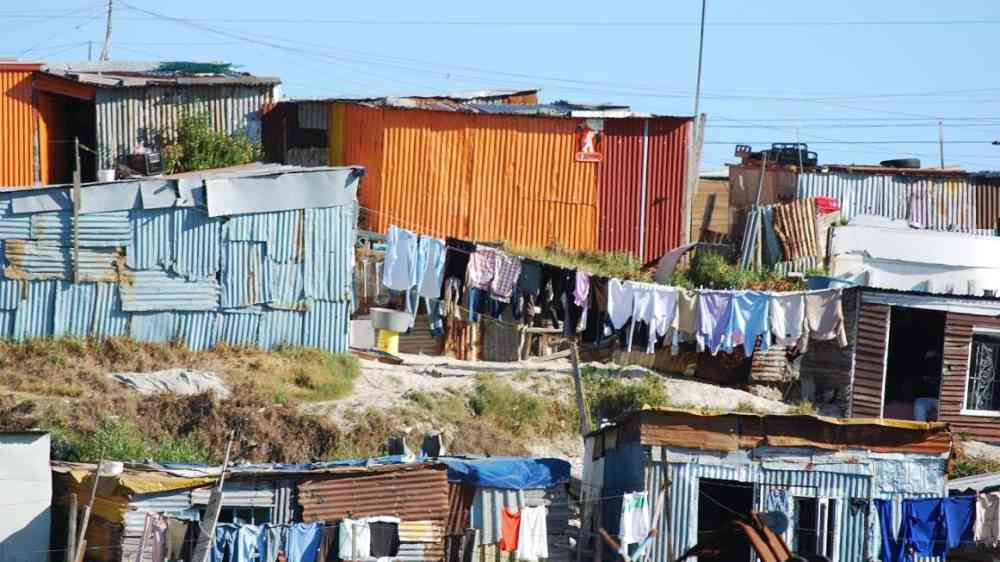

Hot air rises between densely packed homes in Alexandra, the township where Nelson Mandela spent his 20s. Iron roofs soak up the sun’s rays and few trees provide respite from the heat.

A short walk away in Sandton, breezes circulate between widely spaced homes and children play underneath mature tree canopies.

It is an ordinary summer’s day in South Africa’s largest urban area but for residents of these neighboring districts, the temperatures seem a world apart.

Like cities the world over, Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni have stepped up their actions in response to climate change. But city leaders went a step further: they engaged local residents in a citizen science campaign to map exactly which neighborhoods face the brunt of rising temperatures.

More than 100 volunteers ventured out into the streets carrying heat stress monitors. The study, made possible by the National Treasury’s Cities Support Programme, the Swiss Secretariat for Economic Affairs, and the City Resilience Program, established striking facts about heat today and how it relates to historical legacies and future challenges.

Summer in the city: Heat meets history

Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni are part of Gauteng Province, an economic powerhouse region that produces some 35% of South Africa’s GDP. Arriving by plane, visitors often see thousands of blue-flowering jacaranda trees that were planted in the 1920s as residential suburbs expanded.

But the cities, like their populations, are a complex tapestry of influences. Among these are the legacies of apartheid spatial planning practices that left some neighborhoods lush, green, and spacious but others dense and bereft of trees.

Hundreds of readings taken by the campaign volunteers established a clear fact: heat exposure differs based on where you live.

Temperatures across most of the city are 3-4°C higher than in the nearby countryside, but in the hottest neighborhoods — primarily townships that have dense buildings, little vegetation, and where the majority of residents are black — the temperature differential reaches 6°C.

Forward-looking climate modeling showed that the inequalities could become even more acute. If global carbon emissions remain high, the number of hot nights per year is projected to rise from 10 to 40 by 2050 for much of Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni, but from 40 to 100 for its hottest neighborhoods.

Indoor heat exposure is another concern: temperatures inside wood-frame, corrugated-iron homes were observed to be 15°C higher than in modern brick or concrete homes nearby.

Given the close link between night-time heat exposure and hospital admissions, cooler city spaces, health preparedness, and heatwave early warnings are necessary to avoid a potential doubling of heat-related mortality by end-century that would disproportionately affect residents of townships, the elderly, poor people, and those with health vulnerabilities like HIV and tuberculosis.

Taking action: Cooler cities, safer people

So what can cities do to reduce heatwave risks? The campaign produced compelling evidence that actions by urban planners, neighborhood associations, health systems, and weather forecasters can protect citizens and infrastructure during heatwaves.

Bold actions to address heat impacts have already been set out in the Climate Action Plan (Johannesburg) and the Climate Change Response Strategy and Green City Action Plan (Ekurhuleni), which the newly collected evidence will help to further elaborate and concretize.

The campaign measurements confirmed the benefits of expanding green infrastructure in those neighborhoods that lack it: even a few large, shady trees provide sufficient heat stress reduction to make public spaces suitable for outdoor work or sports games during hot spells.

Thermal imagery confirmed that white-painted walls experience surface temperatures tens of degrees lower than dark-painted equivalents; such materials offer a "double win" of lowering temperatures while reducing cooling energy demand that places energy systems under strain.

Driving progress through partnerships and science

With the world’s eyes on this week’s COP27 climate talks, where a short film summarizing this study will be shown, the campaign offers lessons to other cities that are strengthening heatwave preparedness.

First, due care in measurement approaches is needed. There is no substitute for on-the-ground measurement of near-ground air temperature and humidity, the factors that directly translate into heatwave deaths and economic losses.

Second, focus on vulnerable people and the places where heat affects them. Mapping heat is essential to understanding and reversing historical inequalities that magnify the impacts of climate change on affected communities. It is also an essential step to devise effective protection measures, whether through increased vegetation, greener buildings, public health outreach, or heatwave alerts via text message, TV, or radio.

Third, strengthen the "action coalition." Preparing for tomorrow’s heatwaves will require many stakeholders at the table: from health authorities to transport agencies, planners to energy utilities. Citizen engagement in heat measurement helps deepen the partnership.

As global temperatures mount, cities urgently need scientific knowledge and energized partnerships for heat mitigation. Building on such information, climate action can help the citizens of Alexandra get through the next heatwave equally well as the citizens of Sandton.