Counterfactual perspective on the Derna flood disaster

A downward counterfactual is a thought about the past where things turned for the worse. Most thoughts about the past are upward, how things might have been better – but cat modelers need to consider downward counterfactuals.

It is a well-known saying that there is no such thing as a natural disaster. All disasters have a significant human factor component, arising from mismanagement, poor planning, negligence, human error, corruption, etc.

The world’s attention has turned to the tragic events in the Libyan city of Derna, as two dams along the Wadi Derna River failed because of the exceptional rainfall from Storm Daniel, which saw flood waters sweep through the city on September 10.

A report published by World Weather Attribution suggests that the rainfall in Libya equates to a 1-in-300 to 1-in-600-year event.

In terms of potential climate change attribution, it suggests that an event as extreme as that observed in Libya has become up to 50 times more likely and up to 50 percent more intense compared to the pre-industrialized climate.

According to the report authors, the uncertainties for the return periods are very high, but it states that the rain event in Libya is of an event magnitude far outside that of previously recorded events.

In addition, the absence of emergency management processes from effective weather monitoring through to on-the-ground crisis management in Derna, has unfortunately turned this event into one of the largest losses of life so far in the twenty-first century, with expected fatalities ranging from 10,000 to 20,000.

Infrastructure in Libya

According to Hidrotehnika based in Serbia, which was a Yugoslavian construction company in the 1970s, they built the two Wadi Derna dams between 1973 and 1977.

The construction of the dams was part of an infrastructure network to irrigate surrounding fields while supplying Derna and nearby communities with water.

The company’s website states that the two dams, named Derna and Mansour, are clay-filled embankment dams with a height of 75 meters (246 feet) and 45 meters (147 feet) respectively.

Derna had a storage capacity listed as 18 million cubic meters of water, while Mansour had a capacity of 1.5 million cubic meters. The dams were damaged in 1986 after severe storms, but it was unclear whether repairs were completed. The deputy mayor of the city of Derna told Al Jazeera that the two dams had not been maintained since 2002.

Muammar Gaddafi seized power in Libya in 1969, a country with significant oil and gas reserves, and during the early 1980s, GDP per capita for the country’s seven and a half million citizens rivaled other higher-income countries.

But as the economy peaked and troughed over the years, infrastructure investment and even maintenance of existing infrastructure were sporadic. In 2011, the end of the First Libyan Civil War also marked the end of the Gaddafi regime.

A National Transitional Council of Libya was established to plan the country’s post-war transition. Claiming that the Gaddafi regime had left the country’s infrastructure in a state of ‘utter neglect,’ in 2011, Dr. Ahmed Jehani, the Minister of Reconstruction and Chairman of the Council’s Stabilization Team, stated that:

“There is an urgent need to rebuild and modernize our critical infrastructure. Even prior to the revolution, roads, airports, medical facilities, water, and sewer systems outside of Tripoli were largely underdeveloped.”

Regime Change

The Transition Council transferred power in 2012 to the country’s General National Congress which was formed with the task of arranging elections.

A tumultuous period then followed with attacks from competing militias, and the country descended into a second civil war in 2014, which effectively split the country in two in terms of governance; the internationally recognized Government of National Accord in Tripoli for the western side of Libya, and the self-proclaimed Libyan House of Representatives in the east, based in Benghazi.

Attempts to form a Government of National Stability in 2022 have seen the two existing Governments continue to work in parallel. Analysts at the International Crisis Group were quoted by Al Jazeera stating that “… the general state of turmoil means a lot of bickering over the allocation of funds.”

The group added that for the past three years, there has been no development budget, which is where funds for infrastructure should fall into, no allocation for long-term projects, and neither of the two governments is legitimate enough to make big plans; something that curbs any focus on infrastructure.

Even when funds are urgently required by the city of Derna after the floods, and government officials in the east have asked for assistance, the country’s central bank, which is tasked with allocating funds across the country, only recognizes the western-based government.

Overall, the Transparency International Corruption Index provides a comparative country measure of poor governance; Libya ranks near the very bottom at 171 out of 180 countries.

Poor Event Preparedness and Emergency Management Compound the Tragedy

In addition to establishing the level of maintenance and modernization regarding the two dams that failed, strategies for event preparedness and emergency management also need to be urgently examined.

Some five days before the tragic events in Derna, Storm Daniel had already caused record-breaking rainfall in Greece on September 5-6, with a reported 750 millimeters (29.5 inches) falling in 24 hours at a station in the village of Zagora, on the southeastern coast of Greece.

With warnings on Storm Daniel issued by Libya’s National Meteorological Center at least 72 hours before the dam collapse, the center provided advice to the impacted regions to take more care and caution and also urged them to take preventive measures.

Osama Hamada, the Prime Minister of the Government of National Stability which controls eastern Libya including Derna, also declared a state of emergency on September 9.

But in a news report from CBC, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) was quoted saying that the large loss of life could have been avoided if Libya had a functioning weather agency in place.

WMO secretary-general Petteri Taalashe said "If there would have been a normally operating meteorological service, they could have issued warnings. The emergency management authorities would have been able to carry out evacuation of the people and we could have avoided most of the human casualties."

If warnings were received by the city administration, the steps then taken were not informed by catastrophe scenario plans and what steps would need to be taken to protect the people of Derna.

There was confusion as some city residents reportedly received texts to stay at home, others were asked to evacuate, but with most residents sheltering in place, in hindsight, this led to the exceptional loss of life.

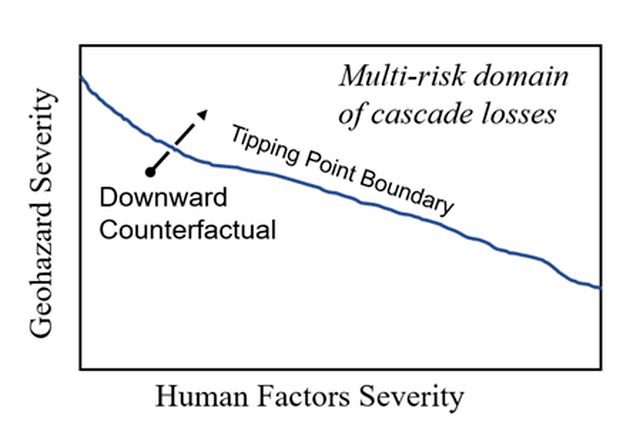

With a high degree of human factor severity, as prevails in Eastern Libya, a geohazard event does not have to be extreme for a transition to occur across the tipping point boundary to a multi-risk domain of cascade losses (see figure below).

But Storm Daniel was a rare Mediterranean hurricane (Medicane), and the two embankment dams in Wadi Derna, collapsed in a domino cascade.

The high flood risk, and need for periodic Wadi Derna dam maintenance, have been pointed out in many studies, including in a report last year by Abdelwanees Ashoor from the Omar Al-Mukhtar University, Libya.

There have also been major flood events in 1941, 1959, and 1968. Counterfactual risk analysis of these historical floods would have emphasized the importance of routine dam inspection and maintenance; a recurrence of the 1959 flood might well have caused dam failure.

There is a natural tendency for systems – whether infrastructure or emergency management strategies, to move towards failure: continual human effort is needed to maintain order and prevent failure, and no country is immune.

On the infrastructure side, for instance, the U.K. ranks number 17 on the Transparency International Corruption Index, but this does not mean that dam mismanagement is not a U.K. safety issue.

Toddbrook Reservoir, located just upstream of the town of Whaley Bridge in the High Peak area of Derbyshire, England, is an 80-foot-tall (24.3 meter) embankment constructed between 1837 and 1840 for water supply. At the time of construction, Toddbrook Reservoir Dam was the tallest dam in the U.K.

Toddbrook Dam was originally constructed with a single spillway at the left abutment of the dam. A concrete auxiliary spillway was completed in 1970 on the central portion of the downstream face of the embankment.

But this auxiliary spillway suffered a serious incident on August 1, 2019, after almost a week of intense rainfall occurring during two separate storm events, the second and more severe of which had an estimated annual exceedance probability of one percent.

According to the local Derbyshire chief constable, the structural integrity of the dam wall was at a critical level and there was a substantial risk to life should the dam wall fail. Counterfactually, the dam might have failed if the heavy rain had persisted, as in June 1872.

An independent review of the failure determined that the most likely cause of the failure of the auxiliary spillway at Toddbrook Reservoir was its poor design, exacerbated by intermittent maintenance over the years which would have caused the spillway to deteriorate.

Downward counterfactual analysis of the 2019 Toddbrook dam near-miss should have encouraged those responsible for embankment dam safety around the world to undertake additional safety checks.

Robust emergency management plans also cannot be overlooked in any counterfactual analysis. If the population of the city of Derna had largely been evacuated before the dam collapse, this would have been a very different tragedy, focused more on the loss of property rather than the loss of life.

It is worth analyzing how emergency management chains collapse in the face of a catastrophe, and this happens all around the world, again and again, in developing and developed countries such as flood events in Germany in 2021 at the Ahr Valley.

With more frequent and severe rainfall events testing water infrastructure around the globe, and what seems to be a pattern of aging infrastructure, neglect, and poor maintenance, coupled with a lack of robust emergency management and the absence of future planning, until more attention is given to downward counterfactuals, and the important lessons to be learned from reimagining history, tragedies such as has befallen Derna will continue to occur.