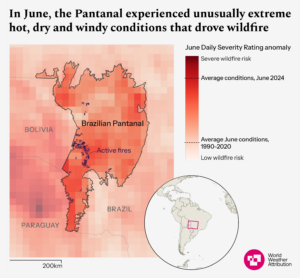

While the peak of the fire season usually occurs in August and September, June 2024 was exceptional, with an estimated 440,000 hectares burned in one month, a significantly larger area than the previous June maximum of 257,000 hectares and far exceeding the monthly average of about 8,300 hectares.

Located at the border with Bolivia and Paraguay, the Brazilian Pantanal comprises more than 15 million hectares. The wetland floods seasonally, from November to April, then drains in the dry season from May to October. It holds a huge range of unique species, is home to many indigenous groups, provides important ecosystem services for the surrounding area, supports the livelihoods of tens of thousands of ranchers, farmers and fishers, and is a vast carbon store.

Indigenous and traditional communities are among the worst affected by the wildfires, as traditional lands are destroyed, cultural practices disrupted and people displaced. Economic activities such as tourism and agriculture are also threatened, with crop losses and livestock deaths. The fires have also killed innumerable wild animals and birds, destroyed vital habitat and made life much more difficult for the animals that were able to escape, as food and water has become increasingly scarce.

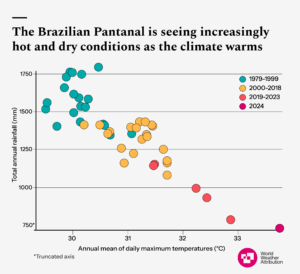

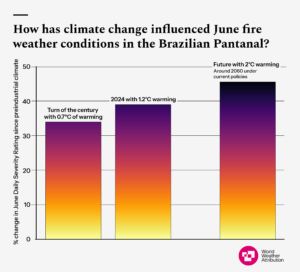

Human-induced climate change is increasing wildfires in many regions of the world, as hot, dry and windy weather conditions increase the risk of fires both starting and spreading. Researchers from Brazil, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the weather conditions that fuelled the Pantanal wildfires, and how the conditions will be affected with further warming. Due to the difficulty of accounting for human activity in both starting and suppressing wildfires, we attribute the fire weather conditions, not the burned area itself.

To illustrate the extent and duration of extreme fire weather in the region, we use the cumulative Daily Severity Rating (DSR) for June, averaged over the Brazilian Pantanal (indicated by the solid black outline in Figure 1a). The DSR indicates how difficult it is to control a fire once it starts and it is commonly used to assess fire weather over monthly or longer periods. The DSR is derived from the Fire Weather Index (FWI), which uses meteorological information (temperature, humidity, wind speed and precipitation over the preceding weeks and days) to predict the expected energy release per length of the fire-front if a wildfire occurs. We focus on the Brazilian Pantanal where nearly all active fires in June occurred; however, including the wider region, which extends into Bolivia and Paraguay, would likely yield similar results.