Northern Kenyans adopt nocturnal life to escape extreme heat

By Abjata Khalif

Atheley, Kenya (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – It is 6 pm in Atheley and as the sun sets, bringing with it a cool breeze, this village in northern Kenya breaks out in a flurry of activity.

People gather outside, schoolchildren shout and play, and the sound of ululating fills the air. But this isn't a wedding or a festival. The residents of this drought-stricken village are celebrating nightfall, because it means they can finally emerge from the shelters that have been protecting them from the extreme heat of the day and carry on with their lives.

"The 'day' has started and people are out of their hideouts ready to attend to their daily chores," says community elder Abdi Abey. "Don't mistake the celebration for a traditional festival. It's a celebration of the changing weather."

Over the past decade, Atheley and other villages in northern Kenya have suffered through a series of every-worsening droughts that have made normal life increasingly difficult. This year, for the first time, temperatures hitting over 40 degrees Celsius during the day have made farming, schooling, healthcare and other daily activities a struggle.

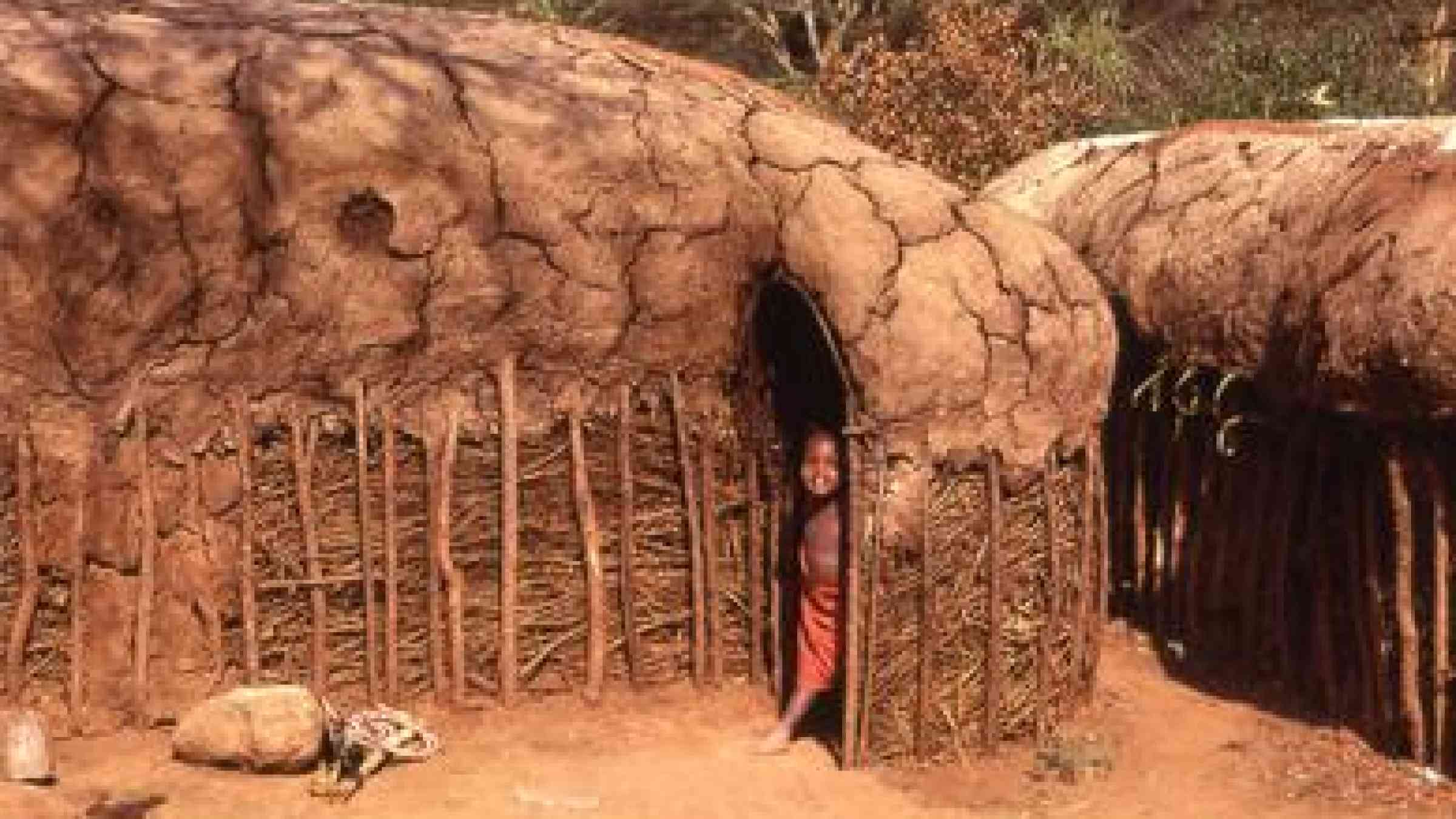

The punishing heat has forced people and livestock to spend their days simply trying to stay cool. Shelters - circular huts made of dried sticks and grass – hold up to 15 people waiting for the night and the chance to get back to work.

NIGHT SCHOOL

With the heat making it hard for children to walk to school and to focus once they are there, the local authorities of Atheley and the neighbouring village of Shimbirey have come up with an innovative way to ensure children aren’t robbed of an education. The answer, they found, is night school.

Normally, Kenyan schools begin around 8 am and end at 4 pm, with two breaks and lunch in between. Now the schools – two in each village – run from 6 pm to 9 pm, with children learning eight subjects divided into 30-minute lessons.

Then the children return home to eat, sleep and do their homework before returning at dawn for another 2-hour session. Before the heat gets unbearable, school breaks up and teachers take to the shelters to mark homework, ready for lessons to begin again in the evening.

This new routine to avoid the sun is only possible by harnessing its power. Solar lamps, charged during the day, provide lighting for the night schools for up to six hours at a time.

SOLAR SOLUTION

Donated to the schools by Dublin-based NGO Afri, one lamp is strong enough to light a room that houses over 50 students and includes a cable for charging the mobile phones that teachers carry with them in case of emergency during night-time lessons.

"The extreme and unbearable harsh temperature has forced us to come up with new ways of offering education at night, when the weather is friendlier and students can attend classes and concentrate," said Abdi Ahmed, a teacher at Shimbirey primary school.

There are even teachable moments to be found in the struggle to keep schools open. "Students are also taught how to charge and use the solar lamps and learn the importance of tapping renewable energy," Ahmed said.

As students hunch over their books at night, groups of women gather in the village to milk cows and goats with the help of more solar-powered lamps. Other villagers wait at their homes for the local nurse to make her way to them to attend to sick family members.

The local dispensary has had to close during the day due to the soaring temperatures, so healthcare happens door-to-door after sunset. "Nurses only operate at night, moving from one homestead to another," said nurse Abdullahi Olat. "It's not an easy task."

The villagers have also had to devise a strict water-rationing plan to protect their scarce supplies from the scorching heat. Atheley's three water points have dried up, so every day a group of women and young men brave the sun to trek to a water source 50 kilometres from the village and bring back more.

For the people of Atheley, delaying daily activities until after sundown is a temporary solution to escaping the worsening heat. But if Kenya's extreme heat continues, villagers may have to get used to the nightlife.

"I have lived in Atheley for 50 years and I have never witnessed such weather conditions, which have turned us into prisoners, forcing us to work at night when we are supposed to rest before another gruelling day of trekking for water and herding livestock," said village elder Abey. "The heat has turned us into nocturnal creatures and we have no alternative but to adapt."

Abjata Khalif is a freelance journalist, based in Wajir, Kenya, with an interest in climate change issues.

(Editing by Laurie Goering)