By Eric Roston

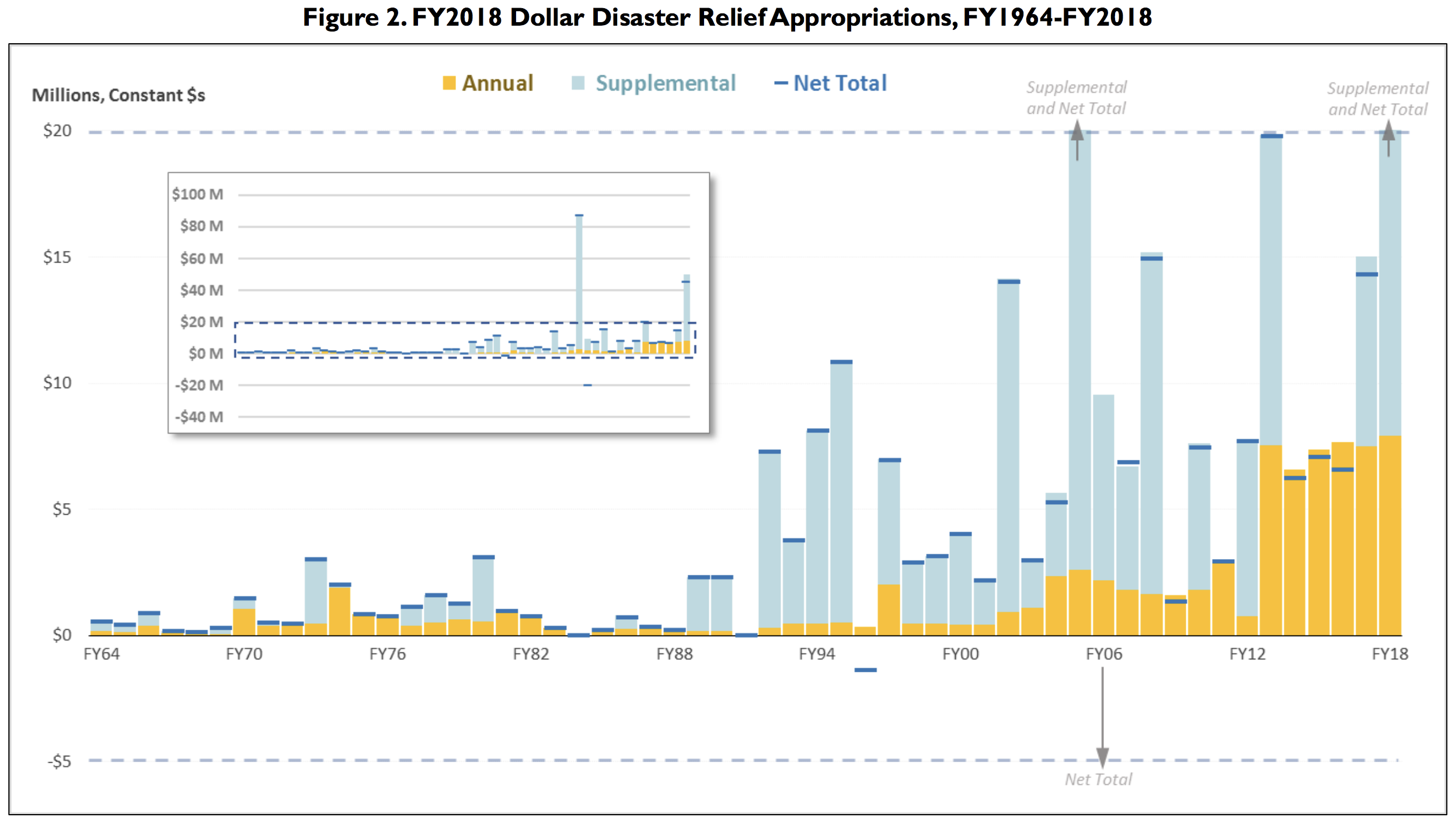

Forecasters are expecting this year’s North Atlantic hurricane season to be roughly average, with about 14 named storms including six full-fledged hurricanes. Last week, the government finally dealt with the fallout from 2018, enacting a $19.1 billion relief package to help U.S. towns and cities still recovering from last year’s natural disasters. Even before that, 2018 had already drawn more emergency funding than any year since 2005, the costliest year on record.

The U.S. is more vulnerable to economic damage from natural disasters than any other nation, according to a recent analysis of global data. For reasons that include its size and location as well as local real-estate development policies, it ranks first among developed countries for the number of lives adversely affected by destructive events. With two long ocean coastlines and a propensity for tornadoes, Americans face more, and more expensive, disasters.

[...]

Source: The Disaster Relief Fund: Overview and Issues. Congressional Research Service

Source: The Disaster Relief Fund: Overview and Issues. Congressional Research Service

[...]

Emergency allocations don’t follow normal budget rules, which demand that spending increases be offset by decreases elsewhere. That makes relief spending relatively easy for legislators, [Josh Sawislak, a strategic advisor on climate economics,] said, compared with preventative investment in infrastructure and services, which would have to be budgeted through normal rules.

“We have a fundamental problem, which is you're trying to come in after and clean up instead of preparing for the thing to happen,” he said.

[...]