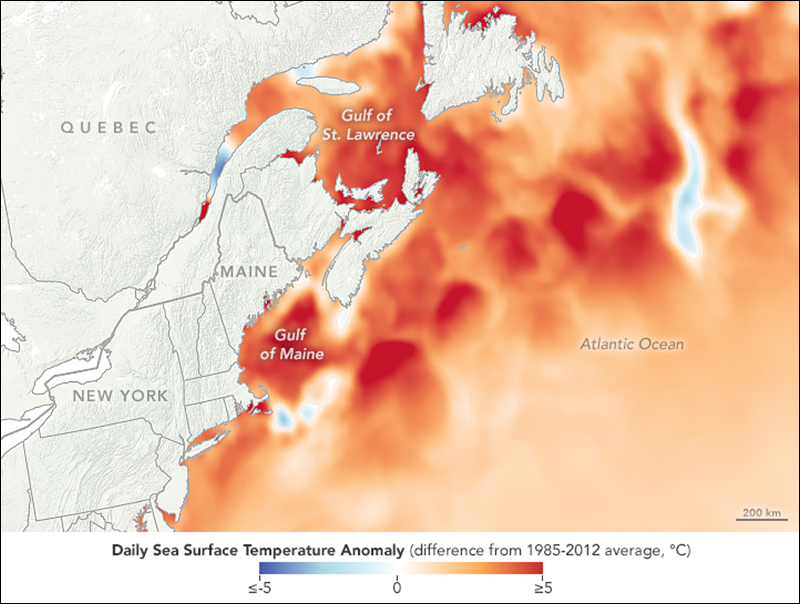

The Gulf of Maine’s location at the meeting point of two major currents, as well as its shallow depth and shape, makes it especially susceptible to warming.

By Laura Poppick

Late last month, four endangered sea turtles washed ashore in northern Cape Cod, marking an early onset to what has now become a yearly event: the sea turtle stranding season.

These turtles—in last month’s case, Kemp’s ridley sea turtles—venture into the Gulf of Maine during warm months, but they can become hypothermic and slow moving when colder winter waters abruptly arrive, making it hard to escape.

“They are enjoying the warm water, and then all of a sudden the cold comes, and they can’t get out fast enough,” said Andrew Pershing, an oceanographer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland, Maine.

Thanks to record-breaking summer water temperatures that quickly transition to cooler conditions, an expanded sea turtle stranding season is just one facet of a new normal for the Gulf of Maine, Pershing explained. And this new normal is a striking contrast to prior conditions.

This year, the Gulf of Maine has experienced only 45 days with what have not been considered heat wave temperatures. Such persistent warmth, scientists warn, can set off a series of other cascading effects on the marine life and fisheries that have historically defined the culture and economy of this region’s coastline.

But what, exactly, makes this region such an acute hot spot for ocean warming? Pershing and others now think they know the answer. They’re using that knowledge to try to predict the impact of future heat waves on marine life in the gulf.

A hot spot for warming

While flying to a conference in 2014, Pershing had an idea. He had been mulling over data showing the Gulf of Maine’s rate of warming over the past decade. That rate seemed high to him, but he wanted to know how it compared to warming in the rest of the ocean.

So, midflight, he pulled together global satellite data. What he found surprised him: This region was warming faster than 99% of the rest of the ocean.

“The Gulf of Maine is way out on the curve,” said Pershing, who published these findings in the journal Science in 2015. Since then, the warming trend has continued. Over the past 15 years, this region has warmed an alarming 7 times faster than the rest of the ocean, according to his research.

The trick now was to tease out just how warm the gulf may become and over what time period.

A weakening “heartbeat”

The source of the Gulf of Maine’s rapid warming lies in the “heartbeat of the Atlantic Ocean,” explained Hillary Scannell, an oceanographer at the University of Washington in Seattle who studied with Pershing as a master’s student.

The heartbeat she refers to centers around the east coast of Greenland, where a large mass of cold water sinks and pulses southward along the east coast of North America, eventually winding its way into the Gulf of Maine. To occupy the space left by this southward traveling Labrador Current, a northward traveling Gulf Stream flows from the equatorial Atlantic to the Arctic, in a circulation system reminiscent of arteries leaving and veins entering a heart.

These two opposing currents brush paths along the Gulf of Maine; that encounter is what makes this region so susceptible to rapid change, Scannell said.

Under “normal” conditions, the Labrador Current easily surges into the gulf, keeping Maine waters cool and the related cold-water ecosystem healthy. But as climate change melts Arctic ice around Greenland, the water in the north freshens. Because fresh water doesn’t sink as readily as denser saline water does, the Labrador Current loses its vigor. This allows the Gulf Stream to nudge its way more prominently into the Gulf of Maine.

Stuck in a bathtub

Aside from this weakening Labrador Current, bursts of warm water have other ways of pooling up in this region, Scannell noted. The Gulf of Maine’s C shape and the broad underwater plateau of Georges Bank keep water blocked in place longer than it would in more free-flowing systems.

Add to that its fairly shallow depth, and the gulf behaves kind of like a bathtub, Scannell said. “If you’re turning down the cold spigot, you’re going to feel more of an effect from that warm water,” she added.

All of these factors set the Gulf of Maine up to be especially susceptible to marine heat waves. And by heat waves, Scannell and other international researchers mean something specific. They defined the term in a 2016 study in the journal Progress in Oceanography as a warming period that “lasts for five or more days, with temperatures warmer than the 90th percentile based on a 30-year historical baseline period.”

Other regions also susceptible to long-lasting marine heat waves include the fringes of the Arctic Ocean, especially around the Barents Sea north of Norway, where the Gulf Stream ends. Another region lies off the coast of Japan, where the warm Kuroshio Current, similar to the Gulf Stream, flows northward.

Despite this susceptibility, no other large-scale region is warming quite as fast as the Gulf of Maine, Pershing said. The 1% of the ocean warming faster is just “pixels here and there,” he explained.

Ecosystems in flux

Scientists don’t know what long-lasting impacts this warming will have on marine life since their understanding of such impacts “has only been opportunistically gained following a few recent events,” said Thomas Frölicher, an oceanographer who studies marine heat waves at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

One such well-studied event off the coast of Western Australia in 2011 demonstrated that heat wave effects can have immediate and long-lasting impacts. In this case, a 10-week heat wave caused habitat-forming seaweed to die, fundamentally changing the temperate reef ecosystem. “Since then, the whole ecosystem hasn’t really recovered,” Frölicher said, explaining that more tropical fish have moved into the system. “It was kind of a tipping point.”

Warming also changes the chemistry of water, including its ability to hold dissolved oxygen, Frölicher pointed out. Warm water can’t hold as much oxygen as cold water can, so heat waves in places that are already oxygen depleted will produce a compounding effect that “probably has a much bigger impact than just one single extreme event,” he said.

The risk of disease also seems to increase in warmer oceans. The infamous Blob—a mass of warm water that amassed along the western coast of North America in 2013 and continued to spread through 2015—triggered a large-scale toxic algal bloom that researchers linked to mass strandings of sea lions during that time.

Seals are also facing threats: More than 1,200 have washed up injured or dead since July along the Gulf of Maine. This unusual mortality event seems to be caused by viral infection, although it’s unclear whether the ongoing heat wave has caused or exacerbated the strandings.

With water warming as fast as it is in the Gulf of Maine, Pershing said, marine heat waves warrant serious consideration as a cause of any unusual shift in marine life.

“The burden of proof is almost flipped to the other side; you probably should be proving that the temperature isn’t what’s causing this unusual thing to happen,” Pershing said.

Shifting baselines

The turtles that were found stranded last week are now undergoing rehabilitation at the New England Aquarium in Boston.

As the region warms, other unusual things have started happening in the Gulf of Maine. For example, a lobsterman found two seahorses in traps he set offshore of the coastal town of Boothbay this summer, an event Pershing called “really remarkable.” These seahorses are typically found only as far north as Cape Cod. Butterfish, another species associated with warmer waters, are also making their way into the Gulf of Maine.

Such shifts in species pose problems for native animals that aren’t accustomed to these newcomers. For example, adult Atlantic puffins have been seen foraging for butterfish to feed their chicks, but butterfish are often too wide for the chicks to swallow, “so it can create real challenges for the puffin colonies,” Pershing said.

Scannell hopes that studying marine heat wave patterns will improve her ability to predict these events. With these predictions, scientists could give those in the fishing industry a sense of what to expect in a coming month or a coming season. But, she noted, such predictions may become more difficult as the days in which the Gulf of Maine is not experiencing a heat wave in a given year dwindle.

Thus, researchers will need to shift their baseline to more accurately describe the current conditions, “or else everything will be a heat wave, and we will have no idea what is extreme for this period,” Scannell said.