Building resilience to natural disasters in the Caribbean requires greater preparedness

By Sònia Muñoz and İnci Ötker

As global warming continues to increase sea-water temperatures, the Caribbean is becoming more vulnerable to increasingly frequent and damaging natural disasters. Policies that build resilience in Caribbean countries—such as strengthening physical infrastructure and putting in place insurance protection—can help minimize the human and economic costs of natural disasters and preserve the region’s majestic beauty.

More vulnerable

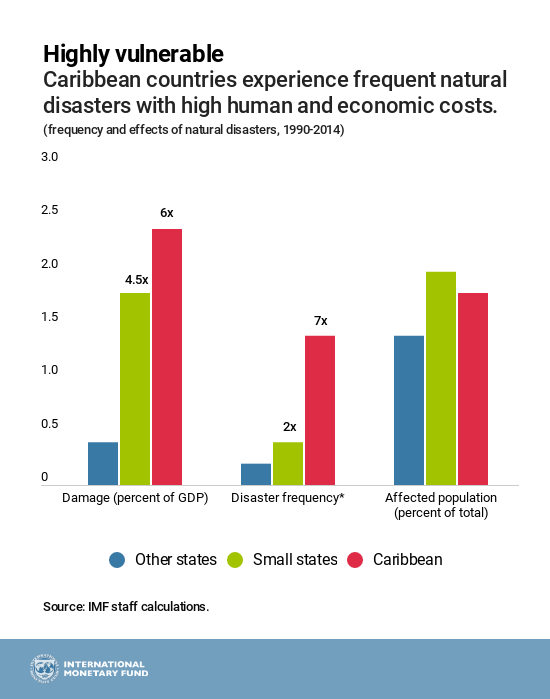

Natural disasters in the Caribbean are becoming more ferocious and frequent even relative to small states. The recent devastations of Category 5 hurricanes Maria and Irma (both in September 2017) demonstrate how powerful storms can lead to widespread destruction, loss of life, and weaker economic growth prospects.

For some disasters, damages well exceed the size of the economy—Dominica, for example, suffered damages amounting to 226 percent of GDP when it was devastated by hurricane Maria. That means that it would take Dominica's output at least 5 years to recover to pre-hurricane levels.

Climate change is expected to intensify these vulnerabilities, as the warming global climate leads to a further increase in sea-water temperatures. This can potentially fuel more storms, and result in rising sea levels, as well as coastal and coral reef erosion—disproportionately affecting the poor and vulnerable living in highly-exposed areas.

Natural disasters take a toll on economic growth, reduce spending room in the budget, and worsen debt, reinforcing the vicious cycle of high debt and low growth prevalent in the region.

Reconstruction costs also take away scarce resources from development and social spending, hurting progress made on these fronts.

Preparing for natural disasters

Policymakers will need to prioritize building resilience to disasters and climate risks, building on three complementary pillars:

- Structural protection to reduce disaster risks, such as through resilient infrastructure, adequate land-use, zoning rules and building codes, and resilient social safety nets;

- Financial protection to reduce the impact of recovery and reconstruction costs on public finances, for instance through risk-financing instruments, such as insurance; and

- Contingency planning and rapid access to financing for speedy disaster recovery.

But building resilient infrastructure takes time and risks cannot always be averted. Securing financial protection, for example, through insurance and provisioning for dealing with the aftermath of natural disasters will be needed to accompany building structural protection. As physical and social structures become more resilient, insurance needs and costs and the need for disaster relief should fall.

Time and investment

The region currently invests little in ex-ante (before a disaster hits) resilience-building and relies heavily on post-storm recovery efforts. Only about 14 percent of disaster-related overseas development is devoted to ex-ante resilience.

Very little budgetary room for investment in resilience building, and limited global financing—well short of adaptation needs—are some of the obstacles the region faces on this front. Complex access requirements to climate funds are also a major roadblock to investing in resilient structures or setting aside dedicated funds.

Weak incentives also play a role. Donors and recipients may find it difficult to pre-commit to a resilience strategy that involves high upfront costs, with benefits visible only in the long term.

Insurance uptake is also low for both public and private sector—with the average insurance gap around 66 percent—reflecting high insurance costs and competing demands on scarce resources. Governments rely mainly on the regional insurance pool, the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility, created in 2012 to provide quick payouts to limit the financial impact of devastation storms for Caribbean governments. But payouts are limited when compared to damages.

Innovative risk-sharing tools such as catastrophe bonds (cat-bonds) have not been issued by Caribbean states, given their complexity and high setup costs.

Shift toward ex-ante resilience building

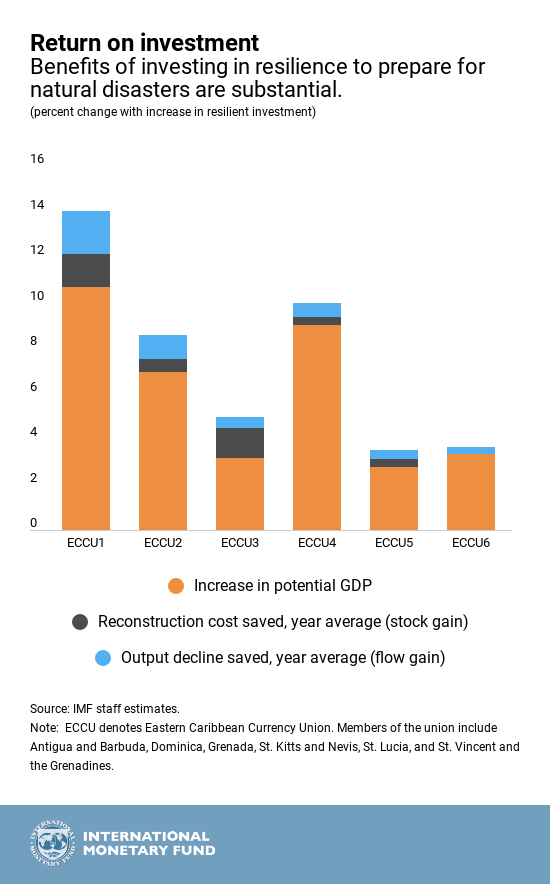

Although ex-ante resilience building implies short-term costs, there are substantial long-term benefits. Ongoing IMF staff research on the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union provides a good example of how a disaster-resilience strategy could have significant payoffs.

In the currency union, where low disaster preparation and high public debt levels represent critical vulnerabilities, resilient public infrastructure investment (such as durable roads, bridges, and sea walls) can raise potential output by 3–11 percent, with an annual growth-dividend of 0.1–0.4 percent.

The analysis also suggests that the short-term costs of resilient infrastructure—estimated to be 25 percent higher than regular infrastructure—and financial protection through disaster funds, insurance, and other risk-sharing instruments, would create a financing gap for the countries. This would make it difficult to attain the currency union’s debt target of 60 percent of GDP by 2030.

On top of necessary fiscal adjustment, bringing the debt to target would require additional concessional financing from the international community, including climate funds. As physical structures become more resilient in the long term, insurance needs would decline to about one fourth of the current level.

A collaborative approach

Strengthening the Caribbean’s disaster preparedness requires a collaborative approach. Having designated resources, while safeguarding debt sustainability, can reduce the need for post-disaster relief assistance over time.

At a high-level conference organized by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank in November 2018, participants supported a coordinated effort for building alliances that address the effects of climate change and support investment in ex-ante resilience.

- Countries are at the center stage. Caribbean countries could design a climate-resilience strategy with support from international financial institutions, multilateral development banks, donors, and climate funds; incorporate expected costs of disasters in macroeconomic frameworks; prioritize actions needed to build resilience; and identify financing needs beside the necessary fiscal adjustment to put their fiscal house in order.

- International financial institutions would support countries in designing resilience strategies. These institutions could support capacity building to deepen insurance and financial markets, analyze risk-management strategies on public debt, and assess the net benefits of innovative risk-sharing tools, including contingent-debt instruments. These efforts will support Caribbean countries’ ability to meet debt-service obligations following disasters.

- Donors could support strong resilience strategies with credible macroeconomic frameworks endorsed by international financial institutions.Concessional financing would be critical to support countries’ fiscal adjustment and resilience-building efforts. Climate funds could simplify their administrative requirements by using endorsement from these institutions of countries' resilience-building and economic policies.