Climate change is increasing the risk of wildfire damage to critical energy infrastructure, according to a new Council on Foreign Relations report that details the physical, financial, and security risks to the U.S. energy system.

By Benjamin Silliman, research associate for energy and U.S. foreign policy at the Council on Foreign Relations

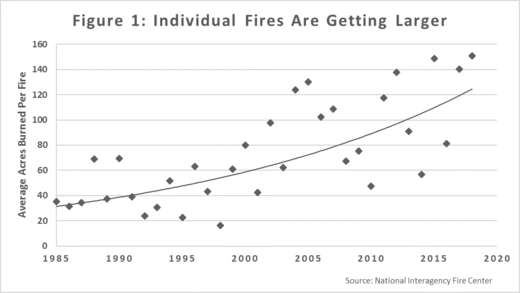

Climate change is increasing the risk of wildfire damage to critical energy infrastructure, according to a new Council on Foreign Relations report that details the physical, financial, and security risks to the U.S. energy system. Severe wildfires have commanded attention in recent years as a destructive force capable of reaching population centers and creating serious financial liabilities. Scientists warn that the severity of wildfires could increase given that climate change exacerbates many of the risk factors that allow fires to spread quickly. While the number of fires each year has not increased in a significant way since 1985 (roughly the same number of fires are occurring now as they did decades ago), the average number of acres burned in an individual fire has risen substantially, making fires that do occur potentially more dangerous and destructive (see Figure 1). Fires spread most quickly in warmer environments where moisture in the ground evaporates quickly. Warming can also contribute to fire risk when premature melting of winter snowpack leads to drier conditions in the spring and summer as groundwater replenishment is diminished. Much of the U.S. West and parts of the South are experiencing these patterns that contribute to the more rapid spread of flames once a fire is started, regardless of its origins whether by natural phenomenon such as lightning or by human accident.

Increased area being burned means that more populations and critical infrastructure could be put at risk. California’s deadliest recent wildfire, the Camp Fire, killed nearly eighty people and wildfires could continue to encroach upon urban and suburban environments even more. The energy industry, particularly the electric grid, is vulnerable to wildfires, the CFR report explains. Faulty equipment and lack of proper fire prevention preparation by Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), California’s largest utility, has left it exposed to liabilities for at least 1,500 separate California fires so far, including seventeen fires that destroyed 3,256 structures and killed 22 people. In January of this year, the utility filed for bankruptcy in the face of the financial problems created in part by wildfire risks. California’s law of inverse condemnation establishes a legal principal that allows a private company to be held fully responsible when its operations destroy life and property while performing a public function.

But electric utilities are not the only energy suppliers vulnerable to wildfire risk. Oil and gas facilities require constant monitoring to mitigate the risk of fire. For example, storage facilities need to be carefully maintained to keep vegetation from growing too close. Nearby fires can also cause disruptions to oil and gas output. The overwhelming Fort McMurray wildfire, that hit the heart of Canada’s biggest oil producing province in 2016, halted the production of nearly one million barrels of oil per day, limiting supply coming into the United States. The gravity of these disruptions makes proximity to an oil field a priority for responders. In June, a relatively moderate wildfire of 40 acres threatened the San Ardo Oil Fields in California. At the time, Cal Fire, the state organization responsible for putting out fires, was already responding to a much larger 2,000-acre wildfire burning to the north. While Cal Fire was able to successfully manage both fires, needing to divert significant resources from large fires was not optimal.

Wildfire interruption of electricity service and oil and gas production effects national security in multiple ways. It not only creates energy supply risks to civilian populations and private businesses, but also to military operations. Military bases in the Western United States rely on nearby civilian energy grids and fuel networks, if these are interrupted so are the bases they power. On top of this, the installations themselves have been in the paths of devastating blazes. In September of 2018, a rampant Sierra Nevada wildfire forced the evacuation of the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center in the region. Earlier this year, a 3,000-acre wildfire burned on a training range in Alaska southwest of Fort Greenly. That area is dotted with unexploded ordinance and represented an unusually dangerous condition for responders. There is also a small risk that fire potential might attract terrorist activity. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in conjunction with local fire agencies has published reports on this possibility, though there is no historical precedent of any such attempt in the United States.

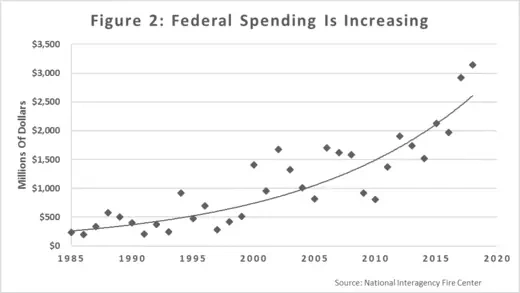

In 2018, President Trump issued an executive order to increase federal resources devoted to forest management and wildfire mitigation. But, to date, there are not enough firemen to handle the current incidents. As more responders are needed to cover the larger areas being burnt, state and local fire agencies are more often requesting military personnel and equipment for auxiliary support. Typically, the costs for controlling, mitigating, and putting out fires are left to individual states, but federal funds are increasingly being used to fight fires. Figure 2 chronicles the trend of increased need for federal assistance, drawing money away from other critical issues. If wildfires continue to grow in size, greater federal spending and intervention on wildfires is likely to be needed.

Wildfires are only one of the natural risks to the U.S. energy system, with significant consequences for national security. As the Presidential campaign season intensifies, more discussion is needed on not only how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate the effects of climate change, but also on the relationship between climate change and U.S. national security, especially as it relates to the energy industry. The risks are immediate and require more attention both in terms of costs that justify greater spending on climate change mitigation and in terms of emergency preparation that is not receiving a high enough priority.