By Nicholas Simpson

South Africa’s National Water week takes place from 16 to 22 March. Dr Nicholas Simpson, from the African Climate and Development Initiative (ACDI) at the University of Cape Town, was part of a research project focusing on why people opt for off-grid solutions in response to disruptions in supply of water or energy and what the effect of those actions might be.

Water security is more often thought about at high levels of water-resource planning, governance and national security – South Africa’s co-dependent relationship with Lesotho illustrates one example of this. However, less thinking has gone into considering how the everyday actions of the general population contribute towards or compromise water security [1].

The Art of Resilience, a research project within the Global Risk Governance Programme, set out to explore just that during the Cape Town drought to consider what household-level actions and practices emerged as people searched for ways to secure access to water.

Climate shocks are increasingly disrupting the ability of the state to deliver key public services, [2] particularly for sectors at high risk from climate variability, like water. Over the past five years, globally significant climate hazards, augmented by climatic changes, have created disruptive shocks, which have undermined service delivery.

California and Sydney saw their electricity disrupted by unprecedented wildfires; Puerto Rico and Beira had their electricity and water systems severely disrupted by hurricanes. After three years of drought, Cape Town came within days of declaring “Day Zero” where large portions of the city would have their water shut off.

Since the frequency and intensity of these events are anticipated to increase in years to come, we were interested to see how people secure their lives when the state appears unable to do it for them. Our observations centred on why people opt for off-grid solutions in response to disruptions in supply of water or energy and what the effect of those actions might be.

Landscape scale disruptions

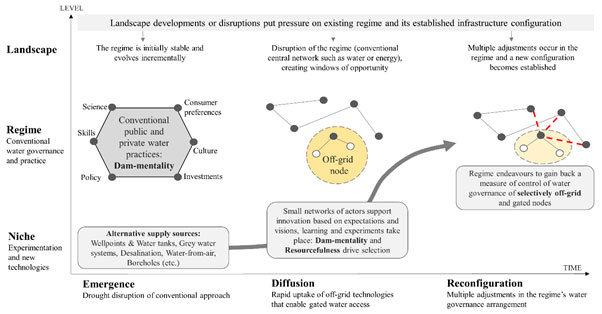

Events like the Cape Town drought are considered “landscape scale” disruptions [2] by scholars. These disruptions can potentially change how we do things and allow for the scalable adoption of innovations that might otherwise be ignored, such as rainwater harvesting tanks prior to the drought [3]. We were interested in the effect of these disruptions on the actions and mindsets of people across various levels of society [2,4].

The conventional approaches of the City of Cape Town were challenged by the potential of a ‘new normal’ in climate risk and their ability to deliver water during severe droughts. Although there was internal resistance, there was a clear shift in the City’s approach to water, and the general population, as the drought became increasingly severe [4].

One of the most obvious changes made by the City was the revision of the water tariff. This was in response to reduced overall water consumption during the drought period, which reduced revenue for the City and threatened the sustainability of the City’s budget [5]. These changes highlight the importance of flexibility and backup systems (redundancy) in infrastructure, finance and governance domains [5].

But there were also many people whose mindsets and actions did not change in response to the drought [3,6,7]. This was most evident in those accustomed to, or requiring, large amounts of water and therefore resistant to reducing their consumption.

Climate gating

We related these climate risk responses to emerging trends, particularly the cascading uptake of off-grid water sources – a decentralising water security phenomenon we call ‘climate gating’ [3]. Off-grid alternatives like boreholes and water tanks were just some of the innovative arrangements that emerged, at extraordinary scales, to secure household-level water access and build private reserves while expanding general reserve margins [3].

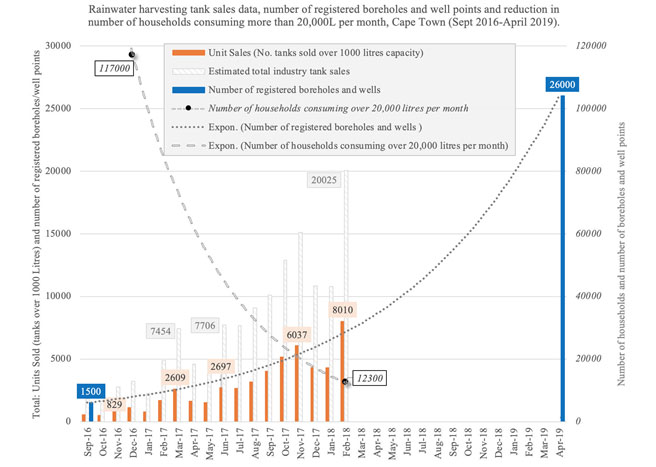

The figure that follows illustrates the chronology of rainwater harvesting tank sales data for a popular tank manufacturer in South Africa, the number of registered boreholes and well points, and the reduction in the number of households consuming more than 20 000 litres per month over the drought period [3].

The securing actions of the private sector highlights the importance of alternatives and backups. Boreholes and rainwater tanks are a means to redundancy – an expression of resilience at a household level. The unintended consequence of these new off-grid capacity arrangements meant that the City was faced with public governance challenges, not least of which was the undermining of revenues collected for water.

Reconfiguration of water systems

We used the Cape Town drought case study to draw attention to the entrenching effect of climate shocks on areas of privilege and inequality of water access [7] – where those with access to the grid (unlike many in informal settlements) decided the grid was not good enough to secure their needs.

The figure that follows sketches how the governance of water has changed due to off-grid supplies and asks questions about the reconfiguration of water systems facing climate disruption [7].

This highlights the mentalities and behaviours that have not changed in the private sectors that were able to secure water through off-grid means. Although the drought has changed mindsets and has enabled novel pathways to new sources of water, we question how ‘climate gating’ has allowed the behaviours of the affluent to remain largely unchanged.

Reliable and equitable access to water will become increasingly challenging in the face of anticipated disruptions to city-wide infrastructures caused by climate change and variability.

The water capacity generated by ‘climate gating’ – whether through boreholes, wells or water tanks – has decentralised water reserves. This has allowed water resilience to become more distributed, diverse and self-healing than an assessment of the Cape Town water supply prior to the drought may have suggested.

The Cape Town drought illustrated the need for the public sector to consider the distributional effects of their actions for the broader populace, particularly those most vulnerable. These observed climate risk responses to water access could signal a more permanent shift towards a dual system in which the rich become self-providers and more resilient, while the poor remain exposed and dependent on the public provision of water.

Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.