Two-fifths of EU agricultural imports could be ‘highly vulnerable’ to drought by 2050

By Ayesha Tandon

At least 40% of the European Union’s agricultural imports will be “highly vulnerable” to drought by 2050, new research finds.

The paper, published in Nature Communications, finds that 35% of locations from which the EU imports agricultural products will see more severe droughts by 2050 due to climate change. This puts the goods that EU countries consume “at risk” and makes the agri-food economy “more vulnerable”, the authors warn.

The study finds that, if moderate adaptation measures are taken, countries including the US will see their vulnerability to drought decrease by 2050, despite an increase in drought conditions. However, it adds that many agricultural imports to the EU are produced in areas with a limited capacity to adapt to climate change– such as soybean from Brazil and cocoa from the Ivory Coast and Ghana.

The authors conclude that the “climate vulnerability” of many parts of the EU’s agri-food economy – including meat and dairy, cocoa, coffee, palm oil-based food and cosmetics – mainly comes from increased vulnerability to drought outside the EU.

The findings show that “climate-driven disasters outside our borders touch our lives directly”, the lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief.

He adds that investing in climate adaptation abroad is “not only a matter of humanitarian concern or geopolitical positioning – it is fundamentally in Europe’s own economic and social self-interest to address climate adaptation in international trade”.

The global food economy

As the world has become more interconnected, international food markets have grown ever more closely linked. The EU, for example, has become a “major player in the global food market and its food system is deeply connected with other regions”, says Dr Teresa Brás – a postdoctoral researcher at the National Laboratory of Energy and Geology. Between 2002 and 2020, the EU’s trade in agricultural products more than doubled and today the bloc imports more food than it exports.

However, as climate change drives more frequent and intense droughts across the planet, many countries are finding it more difficult to grow crops. This can threaten the global food economy and increase the risk of a “breadbasket failure”, in which multiple countries experience large-scale crop failure at the same time.

Dr Ertug Ercin, the director at R2Water, is the lead author of the new study. He tells Carbon Brief that the focus on droughts tends to be national and that not enough attention is being paid internationally:

“Should a severe drought occur in the UK, it would be all over the news headlines and discussed widely via social media. On the other hand, less attention is paid to drought impacts in West Africa or South America, mainly because they are regarded as distant and remote…It is important to raise awareness of why we need to look at changes that are happening outside Europe, as well as within.”

Ercin’s new study assesses the EU’s “agri-food economy” – which includes meat, dairy, cocoa, coffee, food and cosmetic production based on palm oil – and highlights how vulnerable EU imports are to droughts in other countries.

The research selects eight crops – including cocoa, coffee and sugar cane – that need significant amounts of rainfall to grow and are frequently imported to the EU. Using models from the fifth Coupled Model Intercomparison Project, they then determine how drought severity in the growing regions of these crops will change under a low emission scenario (RCP2.6) and an intermediate emission scenario (RCP6.0), which is reasonably consistent with currently enacted global climate policies.

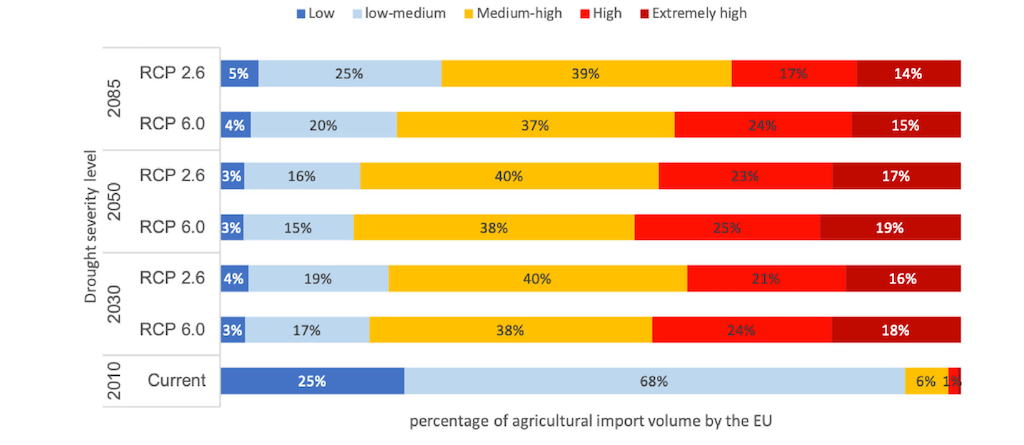

The figure below shows the percentage of agricultural imports to the EU, by volume, that are grown in regions of low (dark blue), low-medium (light blue), medium-high (yellow), high (red) and extremely high (dark red) drought severity. The authors compare drought severity from 2010 with projected severity in 2030, 2050 and 2085 under the two emission scenarios.

The figure shows that in the climate of 2010, around 93% of the agricultural imports to the EU were grown in regions with a “low” or “low-medium” drought severity. However, under the intermediate emission scenario RCP6.0, only 18% of the EU’s agricultural imports will come from locations with low drought severity by 2050.

‘Cross-border climate vulnerability’

As well as assessing drought severity, the authors also consider social and economic factors, including population growth, climate adaptation and global inequality.

To include these factors in their assessment, the authors use the “shared socioeconomic pathway” (SSP) scenarios – narratives about future social and economic development. This study uses SSP2 – a “middle-of-the-road” scenario in which social, economic and technological trends over the coming century do not shift markedly from historical patterns and global population growth levels off by the 2050s.

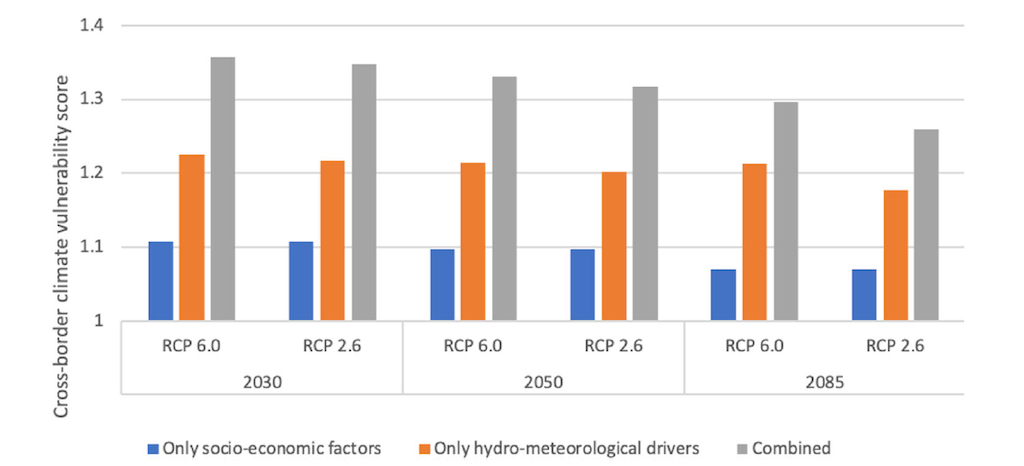

By combining drought severity, rainfall dependency and the country’s ability to adapt to changes, the authors produce a single measure to assess how a country’s vulnerability to climate change changes over time – the “cross-border climate vulnerability score” (CCVS).

A score above one indicates an increase in cross-border vulnerability, while a score below one means a decrease in vulnerability. For example, a score of two means that the country has become twice as vulnerable due to climate change-induced drought.

The plot below shows how socioeconomic (blue) and hydrometeorological (orange) factors could affect the EU’s cross-border climate vulnerability score in the coming century – as well as the two combined (grey). The plot shows results for 2030, 2050 and 2085 under RCP6.0 and RCP2.6.

The plot shows that the EU’s vulnerability to drought peaks in 2030 for both emission scenarios. This is because, under the SSP2 scenario of socioeconomic development, the EU’s population is expected to drop by mid-century, reducing the demand for food, the study explains.

It also shows that drought conditions under the two emission scenarios are fairly similar until 2085. The authors explain that this is because global temperatures are expected to continue rising steadily under RCP6.0, whereas in RCP2.6 they will peak mid-century and then drop.

However, Dr Jonas Jägermeyr – a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, who was not involved in the research – highlights that this study does not use specific crop models.

He notes that his own work shows “fundamental differences between emission pathways and over time by the end of the century” and, therefore, suggests that “including crop models in future work would improve the rigor of climate change impacts”.

Vulnerability mapped

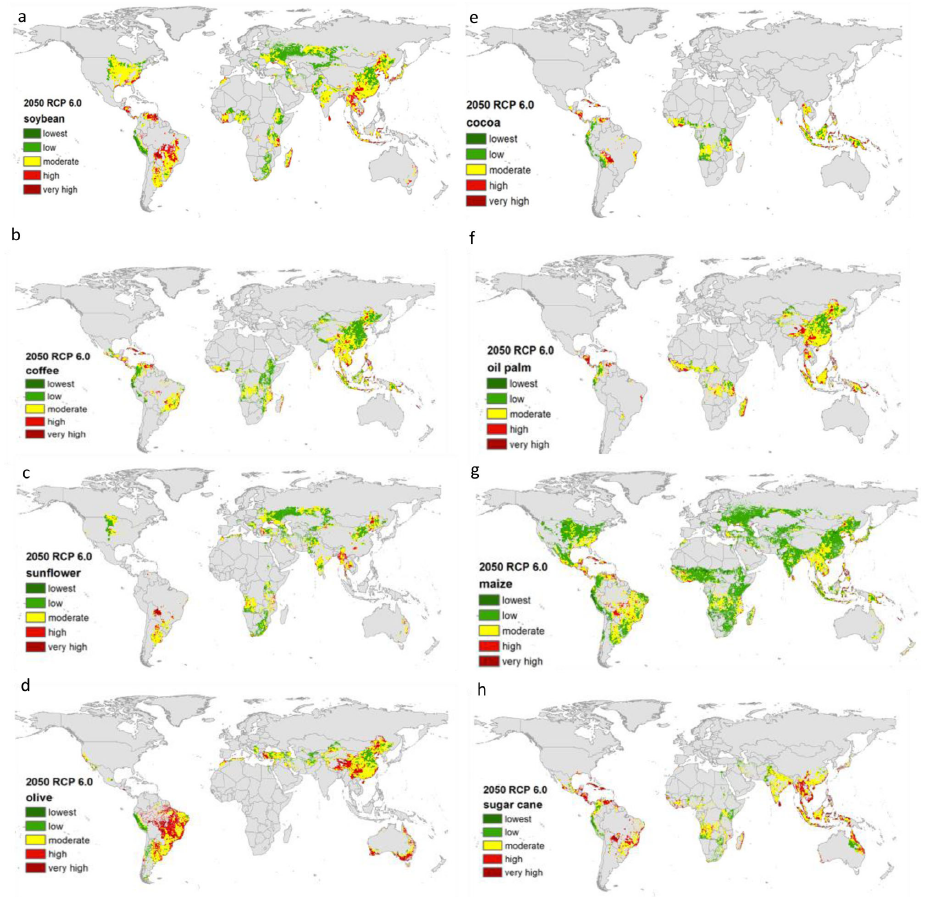

The authors also use the CCVS score – which includes both hydrometeorological and socioeconomic factors – to assess individual crops and countries. The maps below show the vulnerability of the eight crops under RCP6.0 in 2050. Red shading indicates high climate vulnerability to drought and green indicates low vulnerability.

The map shows how varied the different countries’ responses to future drought are. All of the sugarcane used in the EU is grown abroad and the study finds that more than 73% of the sugar cane imports will be “highly vulnerable” to drought by 2050.

Similarly, the authors import half of their coffee from just two countries – Brazil and Vietnam. They find that 44% of the supply locations for coffee imports will be highly vulnerable to drought due to climate change by 2050, with only 28% less vulnerable compared to the current climatic conditions.

As a further example, the EU imports between 30-35m tonnes of soybean every year – mainly from Brazil, Argentina and the US. (Only 0.9m tonnes are grown within the EU.) The study finds that, by 2050 under RCP6.0, around 60% of soybean imports will come from areas with “high” or “very high” vulnerability to drought.

Adaptation measures

The authors also highlight the potential of adaptation measures to lessen a country’s vulnerability to climate change.

The map below shows estimates of cross-border climate vulnerability in 2050 under RCP6.0. Together, the selected countries account for 99% of the total “external rainfall dependency” of the EU. Green shows a reduction in vulnerability between 2010 and 2050, while red shows an increase.

Cross-border climate vulnerability score (CCVS) of the EU’s agri-food economy to drought per exporting country in 2050 under RCP6.0. Source: Ercin et al (2021).

The highest vulnerability to drought is expected in island nations, explains Ercin:

“Historically, south-east Asian island countries, such as Indonesia, have not suffered from drought very much. However, this may change in the future, as shown in the study…These island countries have a low capacity to cope with the adverse effects of future droughts, and all of their agricultural production is rainfed.”

The most vulnerable exporting country in this study is Indonesia, with a CCVS score of 3.5. However, the authors note that, without adaptation measures, such as irrigation, fertiliser, pesticides and tractors, the country would be even more vulnerable – with a CCVS score of 3.9.

Overall, the study finds that most of the agricultural imports by the EU – such as soybean from Brazil and cocoa from the Ivory Coast and Ghana – are produced in areas with low adaptive capacity to climate change. This highlights that European countries should invest in global adaptation efforts – not only for humanitarian reasons, but to support their own economies, Ercin tells Carbon Brief:

“Ultimately, Europe would benefit from directing investment towards these areas to minimise climate impacts – because it is not only a matter of humanitarian concern or geopolitical positioning, it is fundamentally in Europe’s own economic and social self-interest to address climate adaptation in international trade. EU policymakers and businesses have not yet fully woken up to this.”

Dr Magnus Benzie, a research fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that this study is “an extremely important contribution to the small, but growing, literature on the cross-border effects of climate change”. He adds:

“Current assessments of climate risk and the national adaptation plans…largely ignore the systemic, cross-border dimension of climate risk. Therefore, they fail to prepare society for an important dimension of climate risk: one that other studies have suggested is as important, if not “orders of magnitude” more important than direct, domestic climate change impacts.”

Benzie tells Carbon Brief that a recently revised EU Adaptation Strategy “acknowledges, for the first time, the importance of cross-border climate risk”. This study “makes a very useful and informative contribution” to the task of “filling knowledge gaps and enhancing international cooperation on adaptation”, he explains.

The paper also highlights “the current global environmental justice implications of current EU policies”, Dr Kaveh Madani, a visiting professor at Imperial College London who was not involved in the research, tells Carbon Brief. He adds:

“Even if the only thing we care about is the food basket of a European citizen, we now have another piece of evidence which says that, to protect the EU, we need to mitigate climate change and increase the adaptive capacity of the developing nations that provide cheap food. This means that the EU and the rich nations need to provide financial and technological assistance to the poor nations to reduce the vulnerability of global supply chains to climate change.”

The findings are a “call for actions to better deal with the exposure to droughts, not only in the EU but worldwide”, Brás tells Carbon Brief. She adds that this may mean “a redesign of EU food and trade policies in view of higher investment in food imports and market diversification, while promoting climate adaptation, and fair and ethical food policies in non-EU suppliers”.