In 2021, the World Bank Group announced a new core diagnostic report, the Country Climate and Development Reports (CCDRs), to analyze how each country’s development goals can be achieved in the context of mitigating and adapting to climate change. This core diagnostic is being rolled out to every country the Bank Group works in. Through this series we explore different aspects of CCDRs―from their analytical underpinnings to how they are shaping Bank Group operations.

How much climate finance will be needed for each country to transition to a resilient and low-carbon development pathway? That is one of the key questions CCDRs aim to answer. We sat down with Stéphane Hallegatte, David Groves, and Camilla Knudsen to understand how CCDRs assess investment needs.

The World Bank Group recently completed its first batch of CCDRs covering 24 countries. What have you learned so far about climate finance needs overall?

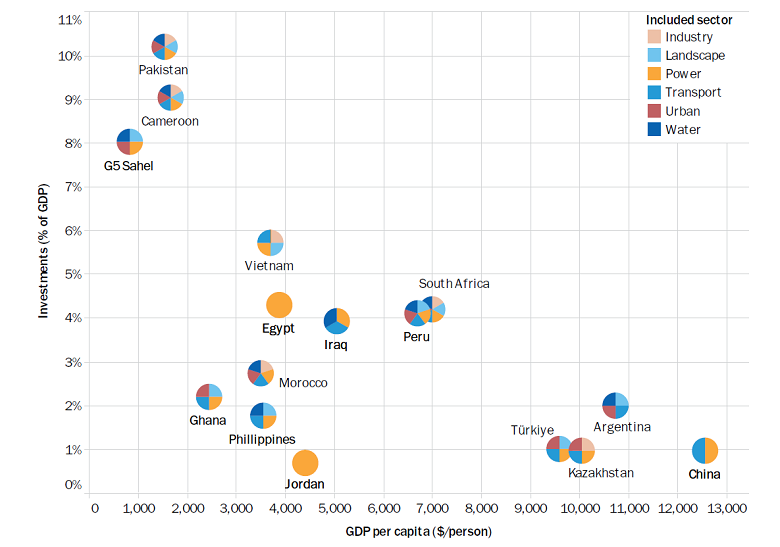

Simply put: climate-development financing needs are larger as a percentage of GDP in countries that have contributed least to global warming, and where access to capital markets and private capital is more limited. Financing needs for climate action across the 24 countries average 1.4% of GDP by 2030, but there are large differences across country income classes: 1.1% of GDP, on average, in upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), increasing to 5.1% in lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) and as much as 8.0% in low-income countries (LICs) (as you can see in figure 1). There is no doubt that international concessional finance will be vital for LICs and LMICs.

Figure 1: Investment needs for a resilient and low-carbon pathway, 2022–30

Note: The sectors included cover each country’s most important needs, making them good (but conservative) proxies for total needs.

That’s quite a range for different countries. How do CCDRs estimate investment needs?

CCDRs use different methodologies depending on what is most relevant to each country. This approach positions CCDRs to support policy debates and prioritization in a given country, although it does make it more challenging to aggregate and compare results.

Having said that, there are some common starting points for all CCDRs: the investment needs we identify represent additional investments needed by 2030 to boost resilience, finance adaptation, and enable countries to undertake low-carbon development. But it is the reference used to define the “additionality” of these investments that differs across CCDRs, since this is largely depending on the development context in each country. That is because CCDRs are focused not only on climate change, but on the interplay between climate change and development.

In many UMICs, such as China and Türkiye, we’ve defined additional investment needs as the difference between a resilient and low-carbon development scenario and a business-as-usual development scenario. These needs are based on the country’s development priorities, but without the same objectives in terms of resilience and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. On the mitigation side, estimates include investments in greener solutions, such as renewable energy, but also ‘negative costs’ from investments that are no longer needed, such as coal power plants or natural gas infrastructure. On the adaptation and resilience side, estimates include the incremental cost of building more resilient infrastructure, not the full cost of the assets. The relatively small additional investment needs for resilient and low-carbon development in UMICs suggest that, in these countries, aligning development and climate magnifies the financing challenges they face, but only moderately.

In most LICs and LMICs, such as Pakistan or the Sahel countries, identified investments go to boost resilience and close existing development and infrastructure gaps, such as lack of access to improved water or modern energy, using the best available technologies to do so. For instance, the Sahel CCDR does not explore how to provide green, resilient energy access to the same number of people, as in a business-as-usual scenario, but rather the investments needed to provide more people with access to green and resilient electricity. CCDRs in LICs and LMICs tend to compare investment needs for a resilient and low-carbon pathway against current investment levels but achieve much better development outcomes than simply continuing current trends. The ‘additional investments’ therefore include investments in greener and more resilient solutions but also investments needed to close existing development and infrastructure gaps (and they are not ‘net’ of non-needed investments). The large additional investment needs in LICs and LMICs show the large financial challenge these countries face to achieve their development goals in a resilient and sustainable way.

Can you dive a bit deeper and explain how CCDR estimates compare with global estimates of climate finance needs?

Sure, let’s focus on global estimates from Beyond the Gap and a recent report by the Independent High-Level Expert Group (IHLEG) on Climate Finance.

The IHLEG report uses country-level-data from Bhattacharya et al. (2022) as well as top-down studies for major categories of climate investments to estimate investment needs in emerging markets and developing countries. It builds on previous assessments, including work of the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Energy Transition Commission, as well as on the adaptation-side work by the United Nations Environment Programme. The report finds that around $1 trillion per year is needed by 2025, and $2-2.8 trillion by 2030, for emerging markets and developing countries other than China. These are total investments (including both development and climate-related needs) while additional investments (climate-related needs only) are estimated at $1.2-1.7 trillion per year by 2030 (with a similar ratio, it puts the 2025 climate related needs at $600 billion).

Beyond the Gap estimates the total cost of closing infrastructure service gaps by 2030 in water and sanitation, transport, electricity, irrigation, and flood protection. One of the explored scenarios is consistent with net zero emissions by 2050 and includes ambitious policy reforms to reduce investment needs and maximize the efficiency of spending. In this scenario, closing the infrastructure gap would cost $1.5 trillion per year by 2030 in capital investments in developing countries (or 4.5% of GDP on average). Without the accompanying reforms, the total cost would increase to 8% of GDP.

The challenge, however, is that these estimates cannot be directly compared with CCDR estimates because they are global, while the sample of CCDR countries is not representative of global needs, and because they use different scopes, baselines, and mitigation and adaptation scenarios.

However, extrapolating CCDR results using the average investment needs by 2030 per income group yields some interesting results. With this simple approach, and being mindful of the differences in methodologies, we estimate annual climate-related investment needs for all low- and middle-income countries other than China at $783 billion per year between now and 2030. This is higher than IHLEG estimates for 2025 ($600 billion), but significantly lower for 2030 ($1.2-1.7 trillion). It is also lower than Beyond the Gap estimates ($1.5 trillion by 2030). So why do we see this difference between the CCDR-based estimates and the global estimates? A few reasons:

First, there are differences in scope and baseline. Estimates from the IHLEG and Beyond the Gap reports are focused on full investment costs to achieve development goals and climate objectives. As mentioned before, CCDRs are focused on the interplay between climate and development and have used different baselines, depending on what appeared most useful and relevant in different countries.

CCDRs and the global reports differ the least in LICs and LMICs where most of the additional investment needs identified in CCDRs would be required with or without climate change. That helps explain why estimates for these countries (5.1% in LMICs and 8.0% in LICs) are close to those identified in the global reports but differ more for UMICs (1.1%).

Second, there are differences in ambition of the scenarios. CCDRs analyze country-specific scenarios, building on countries’ own priorities and commitments, and they take into account what is considered technically, economically, and politically feasible. Consequently, the ambition of the scenarios for mitigation and adaptation differ from most global studies, which apply a more uniform top-down approach.

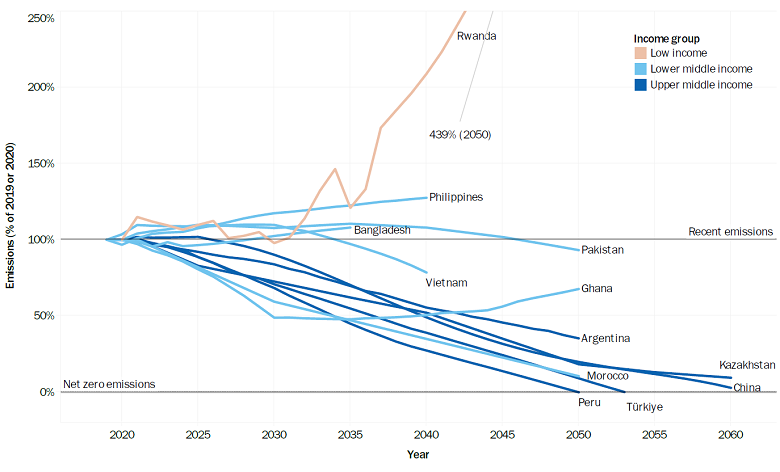

For emission reductions, the first batch of CCDRs presents illustrative pathways that achieve about 70% emissions reductions in the considered countries by 2050, with residual emissions totaling 5 GtCO2e (see figure 2 which shows the emissions pathways for a subset of the CCDRs). Global assessments, such as IHLEG and Beyond the Gap, on the other hand, are typically demand driven and top-down: they calculate what is needed to achieve net zero emissions but without the same focus on absorption capacity issues, implementation challenges, and political willingness and feasibility. If we scale up linearly the $783 billion annual investments to achieve net zero instead of 70% emissions reductions—noting that the incremental costs of the last 30% are likely higher—the annual investment needs for all low- and middle-income countries other than China would exceed $1 trillion, very close to global estimates.

Figure 2: Emissions for low-carbon pathway for CCDR countries

Note: The CCDRs for most LICs did not report emissions pathways, although their estimates of investment needs include actions that would lead to low-carbon development.

Things get even more complicated for adaptation and resilience, since there are no universally agreed upon quantified objectives as there are for global GHG emissions. A desirable level of resilience is a political choice for which there is no single answer. For example, countries or cities at similar income levels have widely different levels of protection against floods. The level of investment needed to boost resilience will be dependent on each community’s risk aversion, but also on many political and technical choices (for instance between protecting existing assets or retreating from at-risk areas). As an illustration, several CCDRs rely on estimates from the World Bank’s Lifelines report, which suggest lower incremental cost of resilient infrastructure than UNEP’s Adaptation Finance Gap Report, used by the IHLEG report. One major difference comes from choices regarding the retrofitting of existing assets: the Lifelines report concludes that systematic retrofitting of all existing assets would not be economical and suggests that retrofitting should be targeted to the most critical assets. Including systematic retrofitting, such as in the Vietnam CCDR, would bring estimates close to that of UNEP’s Adaptation Finance Gap Report.

Finally, there are differences in the timing of investments. Even if studies analyze scenarios with the same target (such as net zero by 2050), there are many pathways to achieving the same end goal. To minimize short-term costs and ensure realistic implementation timelines, CCDRs tend to delay the most expensive actions, thereby reducing short-term costs compared with global studies. Of course, this means investment needs are higher post-2030 but economies will also be bigger—and technologies cheaper—so countries are likely to be better placed to absorb the costs. When considering the time needed to implement the ambitious reforms and investments needed to achieve significant emissions reductions, CCDR teams have considered a delayed action more realistic, even though these scenarios may increase total costs (while reducing short-term ones).

What’s next for CCDRs and investment needs?

Considering the differences in ambition, timing, and methodologies, CCDR estimates of climate finance needs appear to be consistent with global assessments. Their value added is in the granularity provided in terms of the type of investments included, but also in the design of the scenarios that can take into account country-level context and constraints to rapid change. As the World Bank Group continues to develop CCDRs for our clients, and to revise published CCDRs after 5 years, or when circumstances call for it, we will continue to refine our methodologies with the aim of making our estimates more comparable across countries and studies.

Far from a bug that would need to be fixed, however, the diversity of approaches—top-down or bottom-up, goal-driven or intervention-driven—makes the various studies important complements for the design of policies and financing instruments needed to successfully tackle the world’s development and climate challenges.