Why gender equality must be part of global climate finance reform initiatives

Several recent initiatives have targeted the reform of the global finance and development system but they have fallen short on considering gender inequalities. Caren Grown, Anika Heckwolf and Eléonore Soubeyran discuss how a re-envisioning could ensure more inclusive and effective outcomes.

A key objective of the COP29 summit is to finalise the 'New Collective Quantified Goal' (NCQG)- a new financial target for supporting developing nations in their climate action. Total global climate finance increased significantly between 2018 and 2022 from all sources, including domestic, international, public and private, from $0.67 trillion to $1.46 trillion. However, it still falls far short of what is required, particularly in emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs) other than China. Accelerating the global climate finance agenda is therefore essentialto ensure that all countries have the financial resources to address the escalating impacts of climate change and drive a just transition to low-carbon, climate-resilient development.

In parallel to the NCQG negotiations, a wave of reform agendas has emerged since COP26 to overhaul the global climate (and development) finance landscape outside of the formal COP negotiations. Although these initiatives vary in origin, scope and regional focus, they share one critical oversight: a lack of attention to gender inequality and the transformative potential of climate financing that addresses the differential constraints and opportunities for men and women. This commentary examines this gap, why it matters and how climate finance reform could be re-envisioned.

Gender gaps in climate finance reform proposals

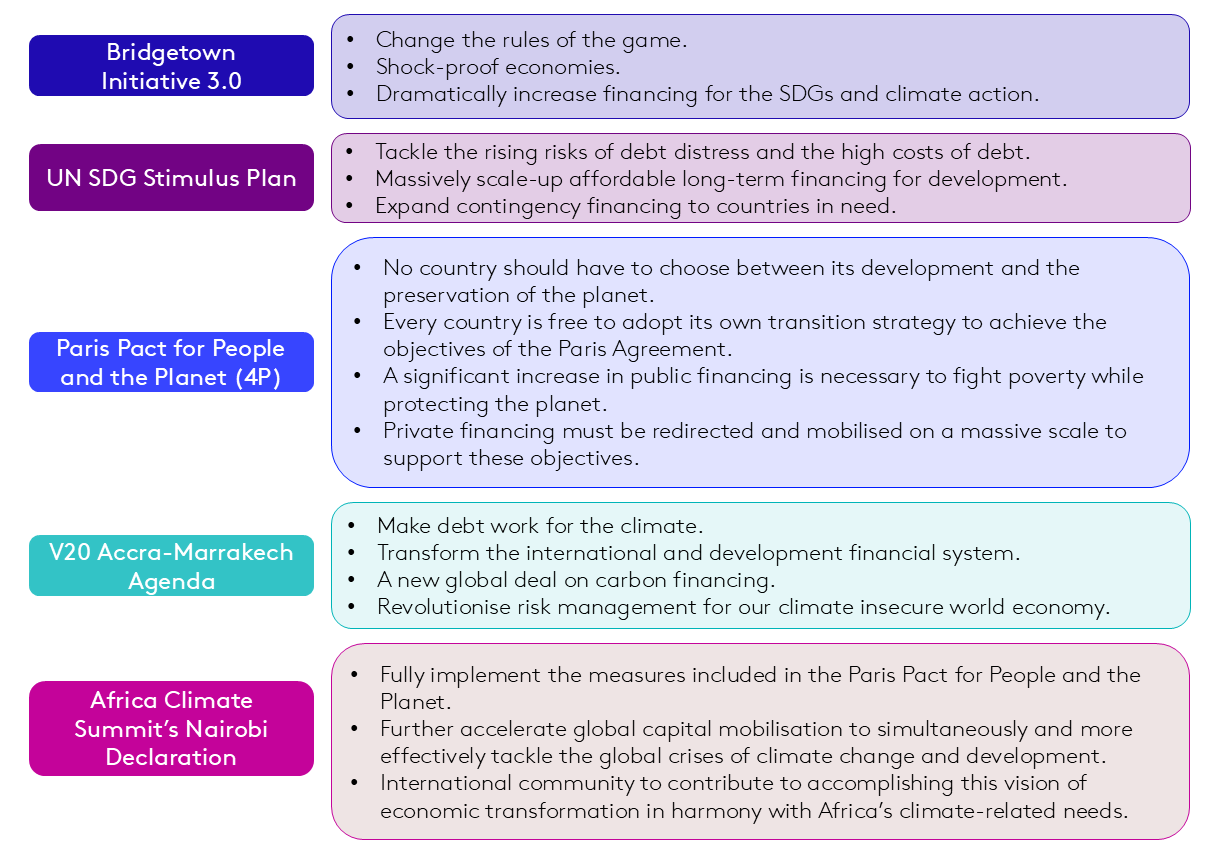

Since 2021, momentum has grown for reforming the global climate finance system, spurred by the only belatedly met $100 billion goal and escalating climate impacts, along with other crises that have deepened inequalities between advanced economies and EMDCs. In response, high-profile initiatives such as the Bridgetown Initiative, UN SDG Stimulus Plan, V20 Accra-Marrakech Agenda, African Leaders' Nairobi Declarationand Paris Pact for People and the Planet(4P) have emerged to create a more inclusive, resilient financial architecture that addresses both climate and development finance (see Figure 1).

While each initiative offers a unique approach, reform proposals broadly converge on key themes: aligning climate action with development priorities, improving emergency liquidity for climate shocks, addressing debt challenges through improved management and relief, expanding multilateral lending, mobilising private sector finance, scaling up concessional funding, innovating liquidity mechanisms, and enhancing access to climate finance and capacity-building.

Some of these initiatives reference gender gaps, but all fall short of tackling them head-on. The SDG Stimulus Plan, for example, briefly references 'women and girls' in the context of poverty but fails to highlight the types of approach that could reduce women's time and income poverty. The Paris Agenda underscores the importance of gender equality in financing, but this commitment is not reflected in actionable strategies. Other frameworks, such as Bridgetown 3.0, the V20 Accra-Marrakesh Agenda and the Nairobi Declaration, make little to no reference to gender gaps or women's participation, despite aiming to support vulnerable populations.

Regardless of whether and to what extent these initiatives specifically take gender equality into account, the solutions they propose may have different consequences for men and women. For instance:

- Untenable debt and debt servicing obligations reduce the fiscal space for governments to invest not only in climate actionbut also in the types of public infrastructure and services on which women tend to relymore than men, increasing their unpaid labour and reducing their earning potential. The initiatives' focus on debt relief (if done in a way that takes gender dynamics into account) therefore provides an important basis for enhancing women's equality and participation in the green transition.

- Women experience greater barriersto accessing private climate finance than men, creating a structural under-investment in women-owned businesses that cannot be rectified by simply making more finance available. Mobilising private finance through dedicated instruments such as gender bonds, different types of insurance instruments and targeted support for women entrepreneurs can play a role in helping to address this imbalance, but any initiative requires the consideration of the systemic barriers that prevent women's access to private finance.

- Currently, the large majority of climatefinance flows into mitigation efforts as opposed to adaptation. Adaptation finance represents only 6% of emerging market economies' total climate finance, but accounts for a larger share in the least developed countries at 38%. Mitigation finance is focused on traditionally male-dominated sectors, such as energy and transport, while women-dominated sectors like small-scale agriculture often lack the finance needed for adaptation and investment in clean technologies.

These examples highlight that without a deliberate focus on the structural drivers of gender inequality, these initiatives risk reinforcing existing inequalities rather than tackling them. By contrast, explicitly targeting gender inequality through climate projects can improve climate outcomes for alland increase the impact of finance dispersed, including by increasinguptake of low-carbon solutions, encouraging economic growthand innovation in new green technologiesand improving agricultural productivity.

Rethinking priorities for the climate finance agenda

Applying a gender lens cannot be an afterthought but must be foregrounded in agenda-setting priorities. We note three gaps to address in current climate finance discussions:

1. Care services and infrastructure

Care infrastructure has always been fragile due to lack of investment in policies, services and resources to support the care of children, the elderly and others. As a result, care systems have largely depended on women and girls undertaking a disproportionate share of their family and communities' caregiving responsibilities, through both paid and unpaid labour - but always undervalued. An estimated 16.4 billion hours per dayare spent on unpaid care work globally, the equivalent of 2 billion people working full-time without pay or formalised support.

Climate change adds stress to this fragile care infrastructure. Climate shocks disrupt and make care work more challenging. This can flare up acutely in cities, where urban infrastructure deficits that manifest in informal settlements and poor access to energy, fuel, clean water or basic social services can make caregiving especially difficult. These problems are increasing as caregivers struggle through more extreme heat and other extreme weather events, and municipalities receive higher rates of rural migrants. Integrating care services and infrastructure into climate finance reform, therefore, is not just about recognising care as a sector but about recognising its foundational role in community resilience and enabling women to participate more fully in climate adaptation and the emerging green economy.

2. Agricultural adaptation

Increasing finance to transform the agriculture sector is particularly important for food securityand the types of activities that women carry out in that sector. In areas across Sub-Saharan Africa with high weather variability and significant dependence on rainfall, women are more likely than men to engage in agriculture in drought-prone areasor areas affected by heat waves. Climate change creates ripple effects throughout food value chains and distribution systems, including losses in the nutrient content of key food crops and increases in foodborne pathogens. Food storage, marketing and transport are challenged more frequently by flooded roads and damaged port infrastructure. Ensuring transformation in agriculture and food security is therefore critical. Targeted financing for sustainable agricultural practices can enhance food security, nutrition and resilience and boost women's ability to adapt in their central rolesin these systems.

3. Social safety nets

Insufficient social protection is underpinned by women's unpaid work to keep families healthy, fed and nurtured, and also fails to reach the poorest workers, including female workers in agriculture and informal employment. Shoring up social protection floors in developing countries requires new thinking about how to estimate the costs of adequate and resilient care systems, systems to protect small farmers, universalising cash transfers and embedding the financing estimates in both development and climate finance discussions. Combining social protection with climate change adaptation, for example, can both guard against income loss and promote more resilient livelihoods. Some countries, including the Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, Bangladesh and Kenya, are building anticipatory climate adaptation mechanismsinto their routine cash transfer programmes which are activated automatically before extreme weather events to help households cope.

Space to do better

That so many proposals to reform international climate finance have come forward, and that so many of them originated from emerging markets and developing countries, is a positive development and opens up much needed space for debate. However, despite growing recognition that gender equality and climate finance are interlinked, this recognition is missing in recent reform proposals. Moving forward, these and similar initiatives should integrate issues critical for gender equality - including care, agriculture and climate adaptation - and ensure that voices advocating for these issues are heard and respected. This is about more than setting quantitative targets. Reforms of the global climate finance architecture, new finance goals like the NCQG, and revisions of countries' action plans expressed in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) must embody a deep commitment to the quality of finance delivered - and integrating gender equality is central to rethinking how and where finance is allocated and distributed.