It won't have escaped many people's attention that the UK has been battered by a series of particularly vicious weather systems recently.

In Reading, where I am professor of climate science at the University, nearly 160 millimetres of rainfall fell over the three-week period between December 15th and January 5th, about a quarter of our annual expected rainfall.

And there has been a range of serious impacts from the severe weather, including damaging gales and properties flooded by rivers that have burst their banks following sustained and heavy rainfall.

Huge waves have battered the coastline where storm surges created by a series of deep low pressure systems and strong winds blowing over thousands of kilometres combined with high tides.

My research looks at how much we can expect greenhouse gases to warm the earth this century and what that means for rainfall patterns worldwide. How the UK's recent weather fits in with what we understand about the climate system and how it's changing are important questions for scientists like me.

So are the recent storms unusual? What's causing them and can we expect to see more of them in the future?

Unusual but not unprecedented

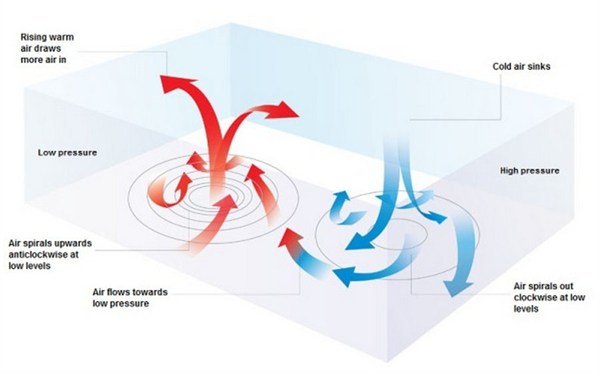

Day to day changes in the weather we see in the UK are dominated by the passage of high and low pressure systems.

Low-pressure systems, in which the air is rising, cooling and condensing moisture as clouds, generally bring unsettled and wet weather.

On Christmas Eve, scientists' instruments measured a near-record low pressure in Stornoway in Scotland. At 936.8 millibars, it was the lowest pressure recorded for 127 years.

The Met Office notes that December was also a very wet month across parts of the UK, particularly in Scotland where it was the wettest month overall since records began in 1910.

However, while unusual, the storminess is not unprecedented. In fact, the many interconnected factors that cause our weather patterns lead to stormy periods every 10 to 20 years or so. For example, the last time as much rain fell in three weeks in Reading was during the Autumn 2000 flooding event.

Each set of events is not usually linked to any specific, single phenomena - it's just the nature of our weather in the UK. But why has it been particularly stormy in the UK recently?

The Jet Stream and winter storminess

The usual suspect is the jet stream, a rapidly moving ribbon of air many kilometres above our heads. It's the jet stream that helps generate and propagate storms from west to east around the middle latitudes of the northern hemisphere, where the UK sits.

The jet stream exists because of the marked contrast in temperature from the warm sub-tropics to the cold sub-Arctic regions. This, combined with the spin of the Earth, leads to the jet stream.

In winter, when the Arctic loses its sunlight completely for weeks on end and cools down rapidly, the temperature contrast is at its highest. That's why we anticipate a stronger jet stream and more storms in the UK during winter time.

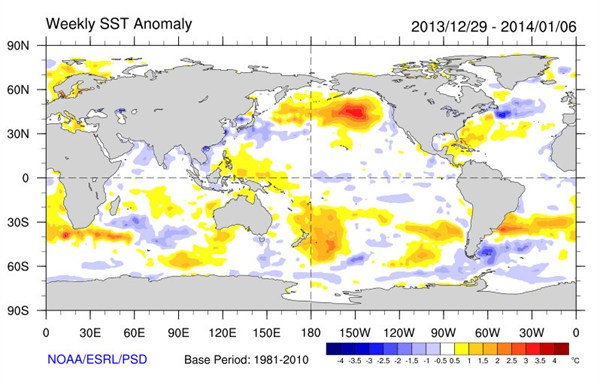

This winter conditions have been somewhat unusual, though. The jet stream has been particularly strong, with estimated winds of over 350 km per hour. Why? To some extent, this is down to a stronger than usual temperature contrast, with cooler-than-average water in the North Atlantic to the east of Newfoundland and warmer-than-average water to the south.

You can see the difference in the map below, where red is warmer water and blue is cooler water.

As the Met Office explained in a blog post last week, another factor affecting the passage of the jet stream is events in the tropics. A narrow band of fast moving winds over the equator is currently in a phase that acts to make our own jet stream stronger, bringing more vigorous storms our way.

A wobbly jet stream

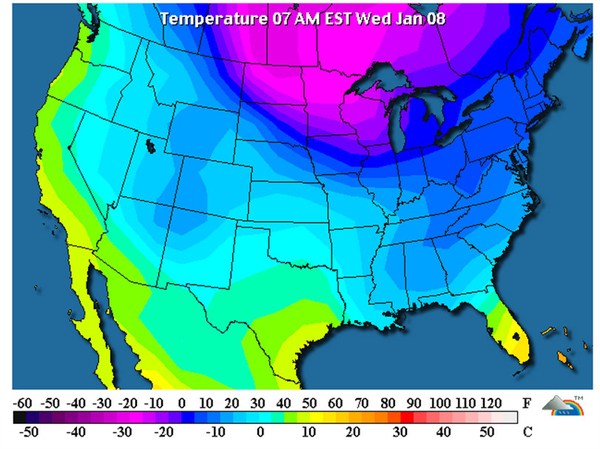

The location and orientation of the jet stream can influence weather patterns right across the northern hemisphere. At the moment, it's sitting in a more southerly position than usual over North America, which explains why we're seeing frigid conditions much further to the south than we might expect.

On the other hand, the jet stream's position is keeping Europe warmer because of westerly winds coming across the Atlantic Ocean. The ocean cools down slowly in winter because of its capacity to retain heat (it takes a while to boil up your Brussels sprouts because of the high heat capacity of water).

There are a number of complicated factors that lead to unusual positioning and strength of the jet stream. So how the jet stream will change in the future, and how those changes will affect storminess or severe winter cold air outbreaks, is far from simple.

Preparing for change

Nevertheless, with the large changes in climate already underway and expected to increase further in the future, it would be surprising if this did not affect our weather patterns in some way.

For example, the Arctic is warming more rapidly than the globe as a whole and so the temperature difference between the pole and mid-latitudes is weakening, with a likely influence on the jet stream and the weather patterns that come with it.

The oceans have a role to play too. Recent research at Reading University and elsewhere indicates a slowing of a deep ocean circulation system in the North Atlantic, known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning circulation. Since this circulation transports vast amounts of energy northwards, a slowing would influence atmospheric temperature contrasts and associated weather patterns, including in the UK.

Risk of flooding set to rise

While individual storms or successions of storms cannot be linked directly to climate change, there are some aspects of a warming climate that are relatively well understood and have implications for the severity of impacts we suffer.

As temperatures rise, basic physics dictates an increase in the amount of atmospheric moisture, which is the fuel for heavy rainfall events. That means whenever we have heavy (and prolonged) rainfall events in the future, we can expect them to be more intense - along with the risk of flooding.

It's these changes in atmospheric moisture that explain scientists' projections of increased risk of flood-inducing storms in the UK in the coming decades. Changes in the jet stream appear to be a secondary factor, and the likely impacts are far less certain.

Scientists are also confident that heating of the deep oceans and melting of land ice will lead to continued sea level rise, which will heighten the risk of coastal flooding and the severity of coastal hazards during stormy episodes.

In making informed decisions to keep risks at an acceptable level, it's important that policy makers take heed of the scientific evidence presented in the recent assessment report from the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - released in September - along with the most up-to-date estimates of the current and future risks. Past events have already demonstrated the risks of not being prepared for these events when they strike.