By Jenessa Duncombe

This year may be the sixth consecutive above-normal Atlantic hurricane season. NOAA released its season outlook today and predicted that it will be another doozy in the Atlantic.

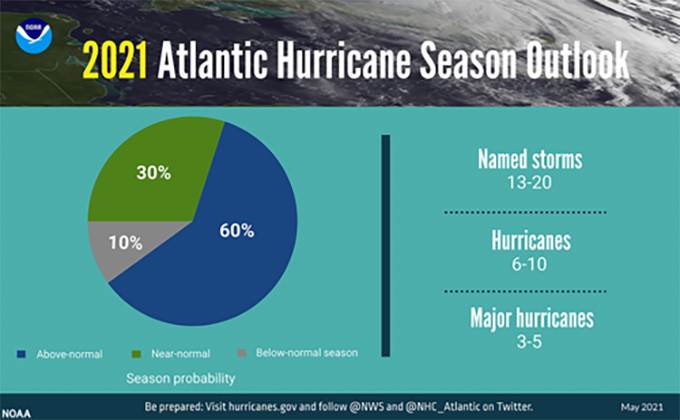

Typically, 14 tropical storms are named during a season. This year? The number will likely hit 13–20.

We could see more major hurricanes than average this year.

We could also see more major hurricanes than average, said Matthew Rosencrans, the hurricane season outlook lead at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. A normal season has three, and this year could bring three to five.

“Climate change has not been directly linked to the frequency of named tropical storms, but it has been linked to an increase in the intensity of storms,” said Rosencrans.

The reason for the higher number of storms this year comes from the ongoing periodic climate fluctuation called the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. We have been in a warm phase since 1995, leading to more storms.

The storm season could be on the more extreme end of the outlook if another large climate phenomenon, the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), switches to its La Niña phase. At this point, ENSO is in its neutral phase, but there is a chance La Niña could develop later this year. NOAA will update the hurricane outlook in August right before peak storm season, keeping any changes with ENSO in mind.

NOAA resorted to the Greek alphabet after they plowed through the allotted list of 21 storm names last year.

Last year was a record-setting year for hurricanes. We had 30 named storms, surpassing the previous record of 28 in 2005. NOAA even resorted to the Greek alphabet after plowing through the allotted list of 21 storm names, ending on the ninth Greek name, Iota, in November. Major hurricanes Laura, Iota, and Eta made landfall and wrought destruction and took lives in Louisiana, Central America, and Colombia.

“Based on our current data and analysis, we do not expect the 2021 hurricane season to be as active as 2020,” said Rosencrans.

Although hurricane seasons vary from one year to the next, findings released last year suggest that greenhouse gas emissions are making intense storms more common. The study, conducted by scientists at NOAA and the University of Wisconsin–Madison, found that the probability of major tropical storms has increased each decade by about 6% since 1979.

There is a 60% chance of above-normal storm activity in the Atlantic this season. Credit: NOAA

It’s easy to point to examples of supercharged hurricanes. The destructive Hurricane Maria that pummeled Puerto Rico in 2017 was made more powerful by warmer air and sea temperatures. And Houston’s massive flooding from Hurricane Harvey in 2017 originated from record-breaking ocean temperatures that summer. In both cases, warming from human-caused greenhouse gas emissions revved the storms’ accelerators.

“If you’re in a hurricane zone, now is the time to ensure that you have an evacuation plan in place, disaster supplies on hand, and a plan to secure your home quickly,” said Benjamin Friedman, acting NOAA administrator.

And don’t forget that rising seas bring destructive flooding, he said. “Make sure your planning focuses on the impact of water as well as wind.”