Direct and indirect losses

Direct disaster losses refer to directly quantifiable losses such as the number of people killed and the damage to buildings, infrastructure and natural resources. Indirect disaster losses include declines in output or revenue, and impact on wellbeing of people, and generally arise from disruptions to the flow of goods and services as a result of a disaster.

Adapted from Understanding Risk: Evolution of Disaster Risk Assessment (GFDRR, 2014) and the UNDRR Global Assessment Report 2015

Economic losses from disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, cyclones and flooding are now reaching an average of US$250 billion to US$300 billion each year for all hazards. Future losses (expected annual losses) are now estimated at US$314 billion as a result of earthquakes, tsunamis, cyclones, and flooding in the built environment alone. This is the amount that countries should set aside each year to cover future disaster losses.

UNDRR, 2015a

The invisible toll of disasters

The estimated insured losses from disasters are a staggering US $120 billion — but they represent just the tip of the iceberg. Visit this page to know more.

What are disaster losses?

The effect of a disaster on people, buildings and society is referred to as the impact. Losses (the result of being deprived of something) are a measure (quantified or not) of the damage or destruction caused by a disaster. The impact of a disaster can, however, be much farther reaching. Wider impacts include longer-terms social and economic effects, for example in education, health, productivity or in the macro economy. The impact of disasters can also generate gains, and not only losses, for some people and economies, for instance the demand for construction material and expertise following a disaster can prosper construction industry. It is therefore necessary to think of disasters in terms of both impacts and losses.

The terms “loss” and “damage” are often used interchangeably. In the context of disaster loss datasets, losses are quantifiable measures expressed in either monetary terms (e.g., market value, replacement value) for physical assets or counts such as number of fatalities and injuries. Damage is a generic term, which is not necessarily quantified, though it does not mean that damage cannot be measured and expressed as a loss. The damage to a roof, for instance, can be translated into monetary terms (the cost of repairs), which in turn can be included in loss datasets.

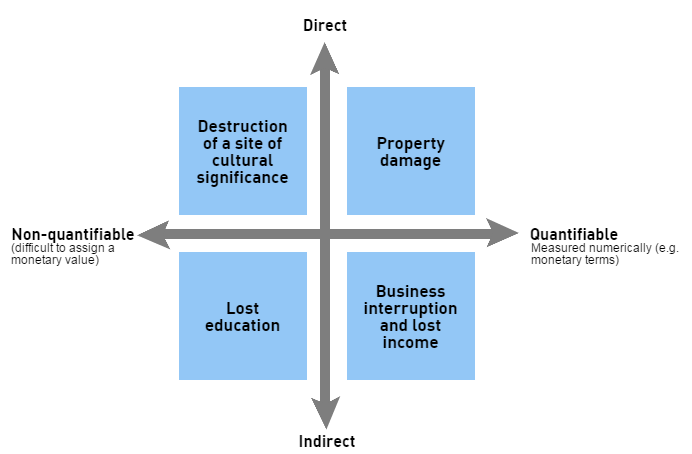

Direct and indirect losses distinguish between the immediate and delayed losses as a result of a disaster. Direct losses refer to the physical or structural impact caused by the disaster such as the destruction of infrastructure caused by the force of high winds, flooding or ground shaking. Indirect effects are the subsequent or secondary results of the initial destruction, such as business interruption losses.

A full consideration of all direct, indirect, and intangible losses would produce much higher loss estimates than the more easily quantified and commonly seen records of direct loss.

GFDRR, 2014a

Many losses are difficult to quantify. For instance, the destruction of culturally significant sites by a natural hazard is a direct loss although quantifying the value of such loss may arguably be difficult. The replacement or real market value of the site and its buildings does not consider the social and cultural meaning or the services provided by the site to its community. These more difficult to value assets are sometimes known as 'intangible losses'. As a consequence, disaster loss databases rarely account for psychological (post-traumatic stress), cultural, and environmental (contamination of drinking water, saltwater intrusion, etc.) impacts.

Visual representation of direct/indirect and quantifiable/non-quantifiable losses.

UNDRR (created using Piktochart)

Why do direct and indirect losses matter?

While it is difficult to calculate a global value, evidence at the country level indicates that indirect losses can surpass the direct costs, particularly if economic resilience is low. Direct losses to the built environment in the Haiti earthquake in 2010 represented 80% of the total direct losses but only 47% of the total (combined direct and indirect) losses. However, indirect losses and the wider effects of disaster loss for low-income households and communities are rarely accounted for.

This is mostly because it can be difficult to anticipate and quantify the potential for indirect losses despite their size. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan and flooding in Thailand offer an example of the global indirect impacts from local events. Although the Japanese tsunami was much more spectacular and had dramatic news coverage; however, the Thailand floods caused much more damage to industrial supply chains on a global basis.

How do we measure direct and indirect losses?

Accounting for disaster losses is a first step towards taking responsibility for, and assessing, disaster risk. Historical losses allow us to develop trends, specifically on the hazards that occur frequently, and ask questions like:

- Are DRR expenditures making a difference in loss trends?

- Are DRR efforts effective?

- Is growing population driving the rise in losses?

- Is climate change affecting losses?

However full scale of disaster losses is still not understood because disaster loss information tends to be incomplete, inconsistent or unreported. Furthermore, disaster losses tend to account for only direct losses.

To identify key hazards, distinguish areas of large losses, and establish loss trends over space and time, disaster losses must be systematically assessed, documented and archived – ideally in a comprehensive manner. Under this scenario, all loss records should be contained within a single system, though (commonly) national agencies document only a subset of hazards and/or losses depending on agency mission and scope. Geological agencies tend to focus on earthquakes, mass movements, tsunami and volcanic activities, whereas national weather agencies are responsible for meteorological and hydrological hazards. Thus, most countries experience a separation in data collection by hazard type or causal agent. International loss data sources, and in particular EMDAT and Desinventar have proven to be extremely useful for practitioners and those doing research at global or regional level as the data is relatively homogeneous.

Compiling and sharing loss estimates through a loss database (also known as an inventory) poses multiple challenges, particularly when consolidating conflicting estimates from multiple sources. Ultimately, most loss inventories contain some form of bias depending on the data source and type of information used in the inventory as well as the type of hazards documented.

While historical losses can explain the past, they do not necessarily provide a good guide to the future.

UNDRR, 2015a

Much of the loss data does not account for the smaller, frequent disasters associated with extensive risk. These losses are absorbed by the people affected, thereby driving further poverty. However, there are a growing number of national disaster databases that provide access to this detailed data on the losses (see UNDRR, 2015a). At the same time, in terms of predicting future losses, historical loss data cannot account for the full range of losses that might occur, particularly in the case of those related to intensive risk because many disasters that could happen have not yet happened. Predicting future losses therefore requires probabilistic simulation of future events, such as that adopted for the UNDRR Global Risk Assessment (2015).

What can we do?

A sound understanding of the drivers and causes of losses as well as their societal, environmental and economic implications enables communities to move from a reactionary to a proactive approach of managing hazards and disaster risks. Understanding these processes helps to underpin strategies and activities for reducing disaster risk.

Loss inventories are tools of accountability and transparency for disaster risk reduction. Loss inventories establish an historic baseline for monitoring the level of impact on a community or country. The impact of individual hazards becomes quantifiable enabling communities to focus their disaster risk reduction efforts on key hazards rather than the last disaster. Resources can be allocated by community or by hazard and used for prioritizing areas of heightened risk (hot spots) and/or by focusing on a particular hazard. However, solely relying on historical losses can underestimate risk. A probabilistic approach uses historical events, expert knowledge, and theory to simulate events that can physically occur but are not represented in the historical record. As such, they provide a more complete picture of the full spectrum of future risks than is possible with historical data.

Last updated on: 18 January 2024

Related stories

Loss and damage finance: A long time in the making but not without its challenges

"A new report from the Finance Working Group of the independent Global Stocktake (iGST) explores loss and damage finance and its place in the Global Stocktake."

"IIED launches a new animation that describes the catastrophic impacts of loss and damage caused by climate change in Sierra Leone."

There will be no ‘green recovery’ for poor countries without loss and damage finance

"A loss and damage fund linked to rich countries’ mitigation efforts could levy new funds to address ‘perfect storm’ of flooding, Covid-19 and economic hardship."