By Paula Uniacke

Last week, heads of state from Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand met for the third Mekong River Commission (MRC) Summit in Siem Reap to discuss the threats to the Mekong River region, among them how to develop effective coping strategies for climate-related vulnerabilities.

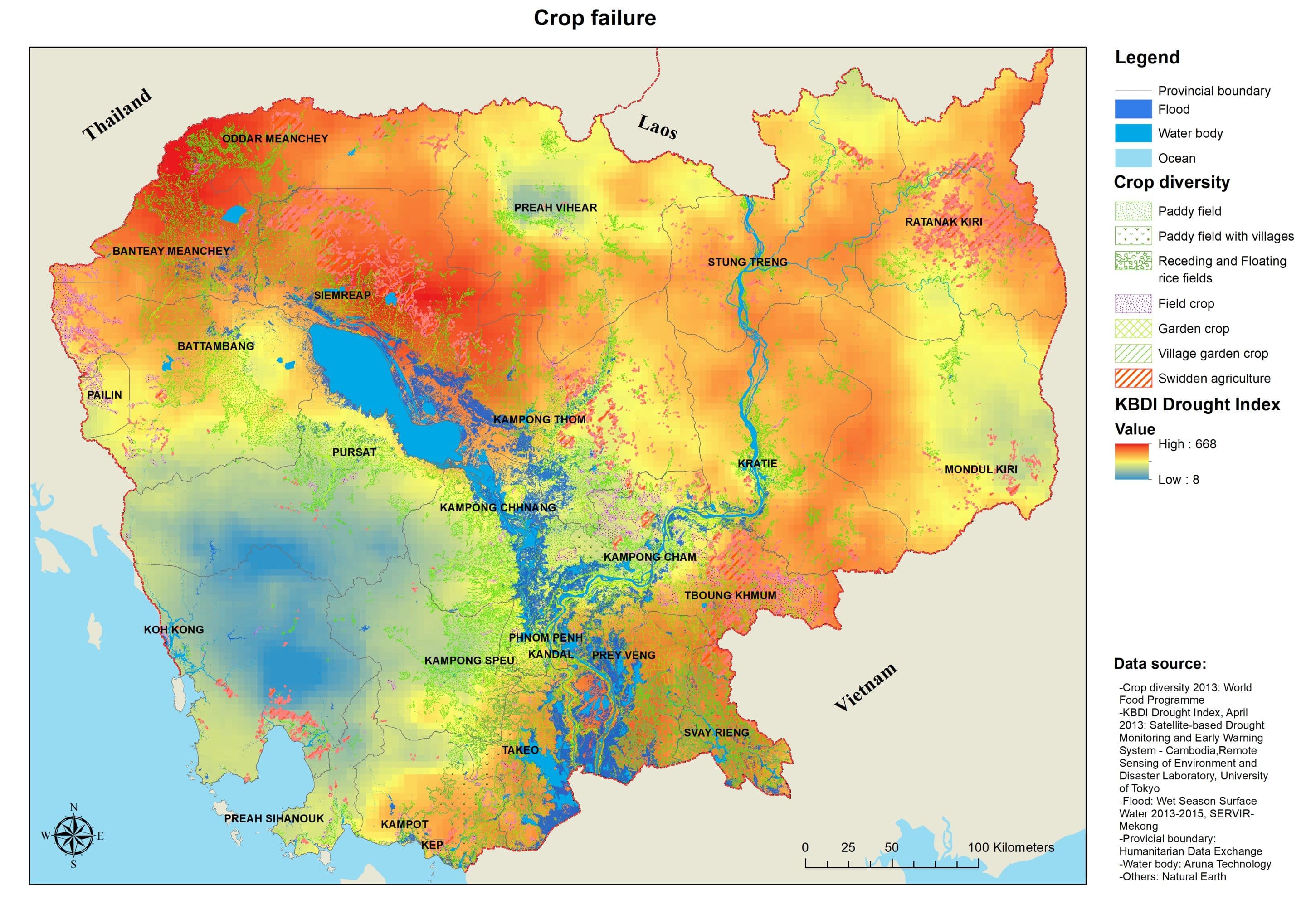

Cambodia is already feeling the effects: the country recently endured a “searing” two-year drought; since 2000, Tonle Sap Lake has experienced the three worst floods and storms in recent history; coastal areas are increasingly exposed to salinity intrusion; and crucial ecosystems are deteriorating. Industrialization and development along the Mekong River Basin only heighten these challenges.

The effects of extreme climate conditions especially impact the rural poor in Cambodia. The majority are dependent on agriculture and fishing for their livelihoods, yet both crop and fish production are threatened as higher temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns result in increasingly severe floods and droughts across the country. This leaves families facing food and income insecurity, and difficult choices regarding the best way to adapt.

While increasing climate variability can have devastating effects on both men and women, it places a disproportionate burden on women in Cambodia. Droughts and floods exacerbate women’s existing vulnerabilities, such as lower levels of income, education, health, mobility, and decision-making power. For instance, flood-related illnesses increase women’s care-taking responsibilities and decrease their ability to pursue income-generating opportunities and other resilience-building activities.

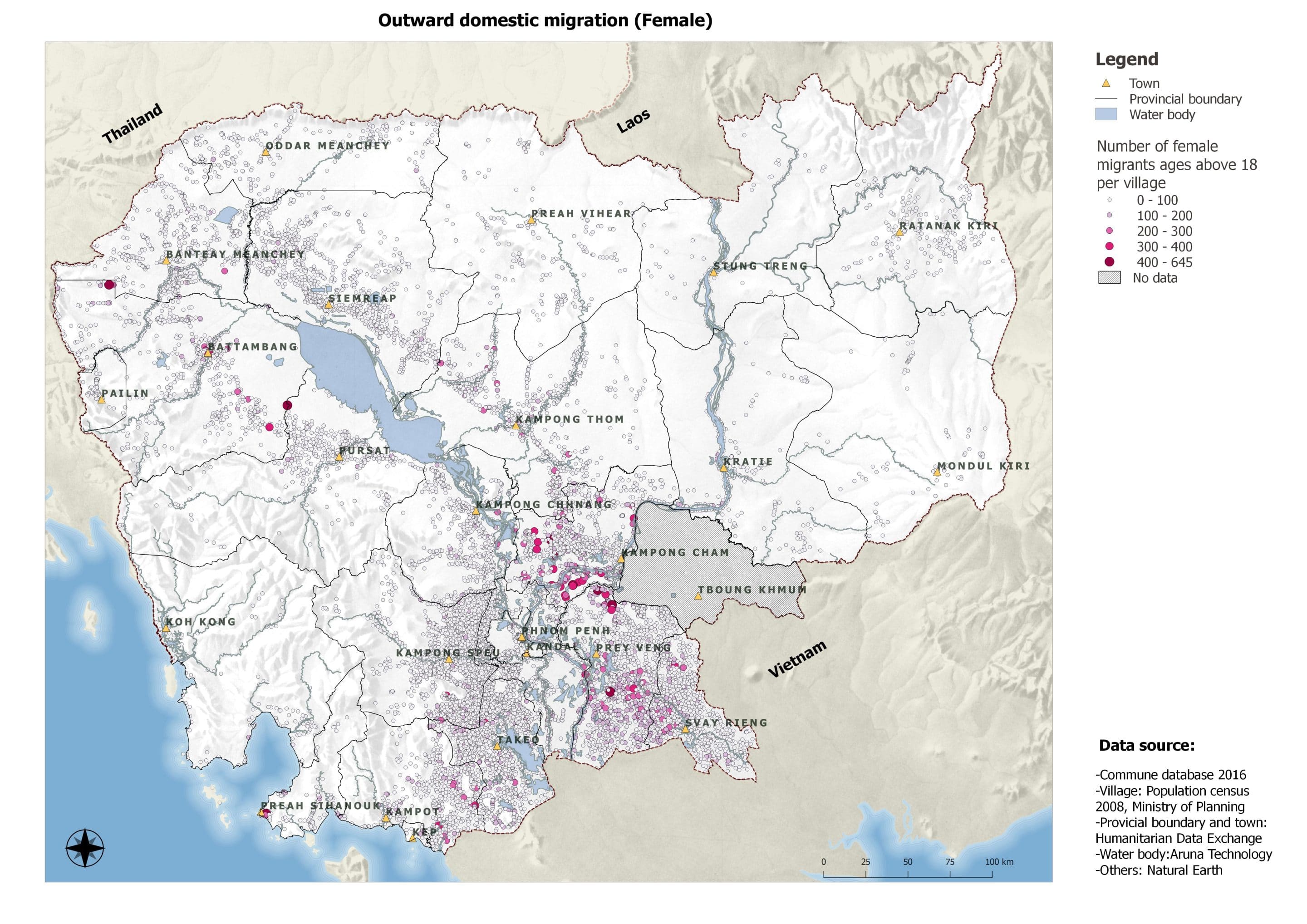

Environmental adaptation is also gendered, as women have less power to influence decisions on how to cope with and mitigate the effects of extreme weather, have fewer resources and capacity to build their own climate resilience, and are impacted differently than men even when they pursue similar adaptation strategies. These gendered impacts also play out with climate-related migration.

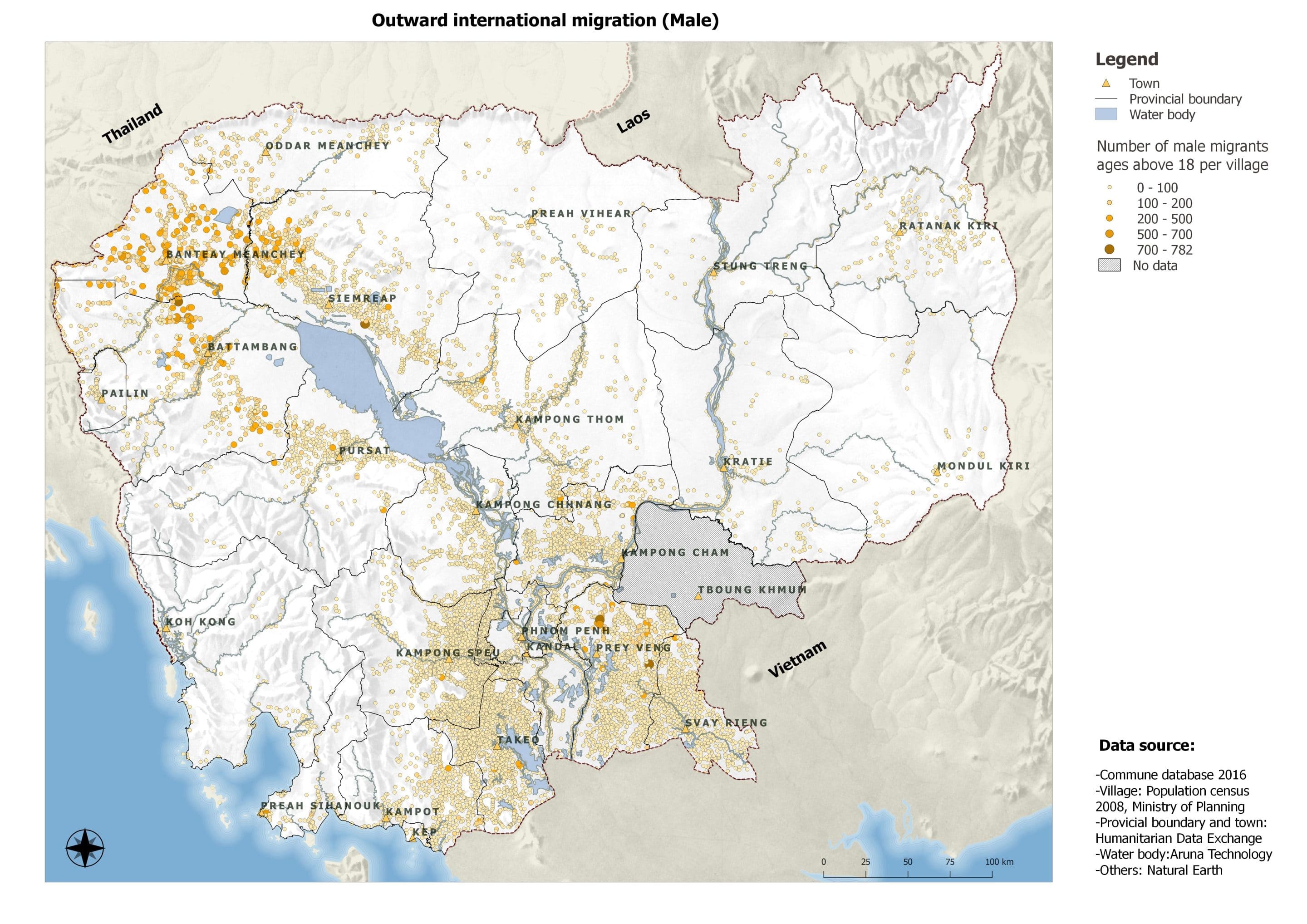

Climate-related vulnerabilities are forcing many Cambodians from rural households to migrate to urban areas or across borders (most often to Thailand) in pursuit of less environment-dependent economic opportunities. While it is often difficult to identify environmental factors as the primary cause of migration—various push and pull drivers interact, so it can be challenging to identify a single economic, political, social, or environmental cause—it is estimated that climate-related migration may affect up to 57 percent of households in Cambodia.

Voluntary migration can be a successful climate adaptation strategy for migrants, their families, and their communities of origin. For instance, remittances may increase household economic stability, health, and ability to adapt to future climate events. However, migration is also a risky adaptation strategy—especially for women. As the Asian Development Bank notes, environmental “impacts and the use of migration as a coping strategy are far from gender neutral.” For female migrants, risks include exploitation, trafficking, and other forms of gender-based violence. The migration of a male family member also carries risks for the women, elderly, and children in their family who stay behind. These can include income and food insecurity, increased workloads, and diminished educational opportunities. While young and working adults migrate in search of work opportunities, children and elderly family members—especially grandmothers—often suffer from poor nutrition, illness and injury, lack of care, and early death.

With Cambodia facing increasingly frequent and severe floods, droughts, and high temperatures, and the link between migration, environment, and gender only recently gaining increased attention from governments and the international development community, efforts to reveal the interplay between these issues are timely and critical. The Asia Foundation and local partner Open Development Cambodia have developed a series of 70 maps to help visualize how different gender and environment-related factors may correlate across Cambodia. The project takes a birds-eye view of a broad range of gender, socioeconomic, migration, and environmental variables to help identify major trends that warrant further examination, research, and action.

For example, when examined side-by-side, the maps on male and female migration, floods, drought risk, and agricultural production give a picture of where both environmental and migration pressures are greatest on men and women who farm rice, which covers over 80 percent of Cambodia’s cultivated land and composes 68 percent of daily caloric intake in the country. These maps do not yet indicate destination or motivation of migrants.

However, when viewed alongside key environmental data, they suggest where it may be possible for development practitioners and policymakers to take a multifaceted approach that together builds climate resilience, advances women’s empowerment and gender equality, and reduces the risks of migration for migrants and the family they leave behind. For instance, in areas with higher levels of cross-border migration and substantial environmental risks, integrating anti-trafficking tools and migrant rights education with efforts to increase women’s access to land, credit, and markets and the use of climate resilient agricultural techniques may help ensure that whether women migrate abroad or remain at home while family members migrate, they have more options.

As Cambodia anticipates an increasingly extreme environment, and leaders in the country and Southeast Asia more broadly commit to reevaluating the environmental effects of development, it is essential to consider both how gender informs environment-related vulnerabilities and how climate and disaster risks impact men and women differently. This includes examining the gender dimensions of key adaptation strategies like migration. Better understanding of these relationships is crucial to developing effective, just, and sustainable strategies to simultaneously build climate resilience and advance gender equality.

The full set of maps including those related to migration are available on Open Development Cambodia’s website.