Dam-failure flood risk in California: How to manage low-probability hazards

Every year, damaging floods strike somewhere around the world, including sometimes in California like during winter 2022-23. Even a house with just a 1% chance of flooding each year (by the so-called “100-year flood”) has a 26% chance of inundation over a 30-year mortgage. Other natural hazards have much lower probabilities, but would bring more catastrophic consequences. These threats are much more challenging to plan for; dam failure and associated flooding is one such hazard.

Over the past 100+ years, California has built over 1200 dams, which impound ~42 million of acre-feet of water statewide[1]. The probability of a dam failing in any one year is very small but no dam is “failure-proof.” While California hasn’t suffered a catastrophic dam disaster in recent history, the 1928 failure of St. Francis dam killed over 400 people. And the failure of the Oroville Dam spillway in 2017 caused the evacuation of more than 180,000 people and was a harsh reminder of the importance of dam inspections and maintenance. Mitigation strategies for low-probability, high-consequences hazards differ from mitigation of other kinds of threats.

Across the United States, over 4.7 million home and business owners currently hold insurance policies underwritten by the National Flood Insurance Program, or NFIP (as of 10/31/2023), covering almost $1.3 trillion in property. NFIP policies cover only a small fraction of total US property exposed to flooding, with climate change further increasing risk in many areas (Wing et al., 2020). However, these numbers miss another key dimension of US flood exposure – properties owned by the states and other public entities.

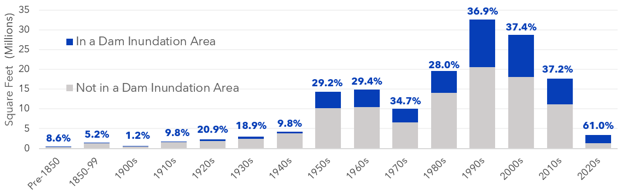

We obtained information on California’s state-owned buildings from the Department of General Services (DGS) . This large and attribute-rich data source has some major gaps, such as most University of California structures. The DGS property inventory contains information on more than 24,000 state-owned structures statewide, totaling about 250 million ft2 of building floor space. This inventory includes building structure data, butdoes not include roads or bridges or other such infrastructure. The largest category of structures by square footage are managed by the California State University, followed by state prisons. The age distribution of California’s state-owned facilities reflects the State’s history of growth and infrastructure investment, with more than 25% of structures built during the 1990s and 2000s.

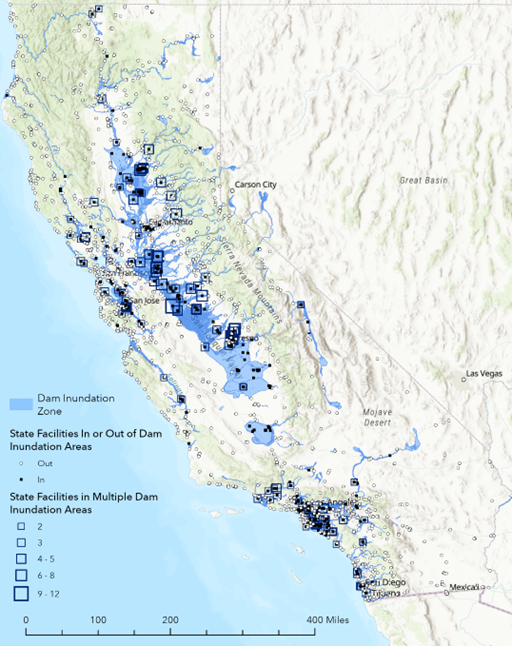

For the broader study, we separated risk from (1) “normal” flood events – i.e., resulting from extreme rainfall or snowmelt – from (2) inundation should one of California’s large dams break, which is the focus here. Dam-break inundation maps are publicly available for all dams operated by the California Department of Water Resources and by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The other major operator of dams in California is the US Bureau of Reclamation. Bureau dam-failure inundation maps are currently not publicly available. For this study, we had extensive discussions with Bureau of Reclamation staff. Despite our offer of a non-disclosure agreement or other terms to allay the Bureau’s concerns, they were unwilling to share inundation-area information, arguing that such information could compromise national security.

Given the available dam-failure data, we identified 3855 California state-owned structures located within one or more dam inundation areas (Figure 1). These properties include 63.3 million ft2 of floor area, or about 25.8% of the statewide total. Structures include downtown Sacramento office buildings, migrant farmworker housing centers, prisons, DMV field offices, and many other building types and uses. Individual dams cast large shadows over the areas downstream, for example Folsom Dam on the American River, failure of which would threaten downtown Sacramento.

We conservatively estimated values of California state-owned buildings in these dam-inundation areas at a minimum of $11.56 billion, which excludes other public infrastructure like roads and bridges. Furthermore, of the 3855 state properties at risk for dam inundation, 1622 properties are in more than one inundation area (~42% of the total).

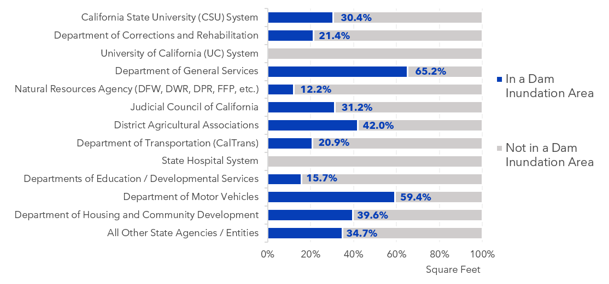

Figure 2 shows the proportion of California state-owned properties in dam-failure inundation zones by agency. The Department of General Services, Department of Motor Vehicles, and District Agricultural Associations have the highest share of properties in dam inundation zones (65.2%, 59.4%, and 42%, respectively). A considerable proportion of properties in the California State University (CSU) System are at-risk for dam inundation. Figure 3 shows increases in the proportion of state facilities in dam-failure inundation areas over time as buildings were constructed in these zones.

Threat from dam-failure vs. “normal” river flooding

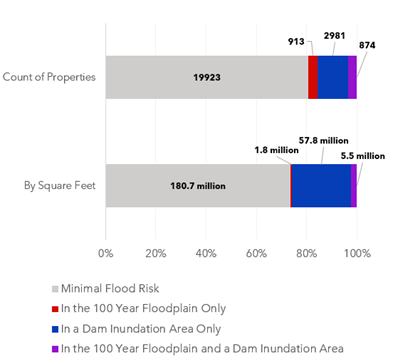

A total of 4768 California state-owned structures are either in FEMA’s current mapped 100-year floodplain, in one or more dam inundation areas, or both (Figure 4). These properties total 65.1 million ft2, or about 36.0% of the statewide total. Of those, 874 properties are exposed to both hazards, comprising 5.5 million ft2 of floor area, or approximately 2.3% of the statewide total.

“Risk” is commonly defined as the probability of an event multiplied by the magnitude of consequences should that event occur. In the case of riverine flooding, even floods with just a 1% chance of occurrence each year are frequent enough that “mitigating” (fixing) that risk is usually cost-effective and sometimes even mandated by law. In the US, each $1 spent on flood mitigation saves an average of $6 in damages avoided). In contrast, some types of hazards have probabilities so low that, however large their consequences, most investments in mitigation do not make sense. No threat could have greater consequences than the impact of a meteor into the earth. But despite what Hollywood blockbusters – and some fringe-science theories – suggest, there is no evidence that any human has ever died due to an impactor from space. Calls for multi-trillion-dollar space interceptor systems don’t pencil out (Pinter, 2008).

In the context of managing and mitigating dam-failure risk, the low probability of failures suggests that society need not – and in California, arguably cannot – entirely avoid building downstream of dams.

However, the catastrophic consequences of a dam failure means that engineers and planners cannot ignore that possibility. The key impact is the potential for loss of human life, and any such threat requires preparatory action. At a hard minimum, owners and operators of dams in California and worldwide must promote broader public awareness of dam-failure risk.

The analysis here of exposure to dam-failure inundation excludes several of California’s largest dams, including Shasta and other Central Valley Project dams operated by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The Bureau asserts that they cannot share flood information below their dams because this information would compromise national security. We question that assessment, and further propose that public awareness of potential risks is paramount to reducing loss of life in a catastrophic event. We encourage the US Bureau of Reclamation to join their peer agencies who make modelled inundation areas available to the public.

After transparency, the public must demand unfailing vigilance and maintenance investment from its dam operators. As the Oroville crisis in 2017 highlighted, when it comes to certain hazards, we prepare for the fastball, but it’s often the curveball that hits you in the side of the head. The greatest danger in dam safety can be complacency.

Finally, we suggest that planners and state leaders consider the nature of structures in dam failure inundation areas. A DMV office located downstream of a big dam may be acceptable and, in some locations, unavoidable. But some critical facilities require a different calculus. Facilities such as fire stations, hospitals, and high-security prisons with resident populations that cannot easily be moved perhaps should avoid dam-inundation zones in the first place. Mitigating exposure after the fact is always much harder than avoiding that exposure from the start.

Conclusions

Hundreds of thousands of California residents live and work in areas that would be inundated, perhaps catastrophically, if a dam upstream were to fail. State-owned buildings are part of this exposure. Our analysis quantifies this dam-failure risk and explores how society can manage such low-probability, high-impact hazards.

Given available dam-failure data, we identified 3855 California state-owned structures within one or more dam inundation areas, comprising 63.3 million ft2 of floor area, and valued at a minimum of $11.5 billion. In California, it is likely impossible to avoid infrastructure located within dam-inundation areas, highly unlikely to remove such infrastructure, and usually not even cost-effective to engineer these structures against the catastrophic hydraulics of a dam break. However, it is reasonable that any new critical-facility construction – such as of fire stations, hospitals, or high-security prisons – might reasonably be steered to safer locations.

Dam operators need to acknowledge that dam failure has a non-zero probability, and part of managing that “residual risk” is transparency. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation should recognize that dam-failure inundation maps pose no real threat to national security – the locations of the dams themselves are well known, including on Google Earth, and inundation maps downstream of those dams provide no information useful to any terrorist. On the contrary, public awareness requires that the low-probability threat of dam inundation be advertised and instantly available if – however unlikely – events such as in 1928 at the St. Francis Dam or in 2017 at Oroville should be repeated. Finally, public agencies at all levels: local, state, and federal, should continue their vigilant monitoring and investments in maintenance of critical infrastructure like dams.